Digestion

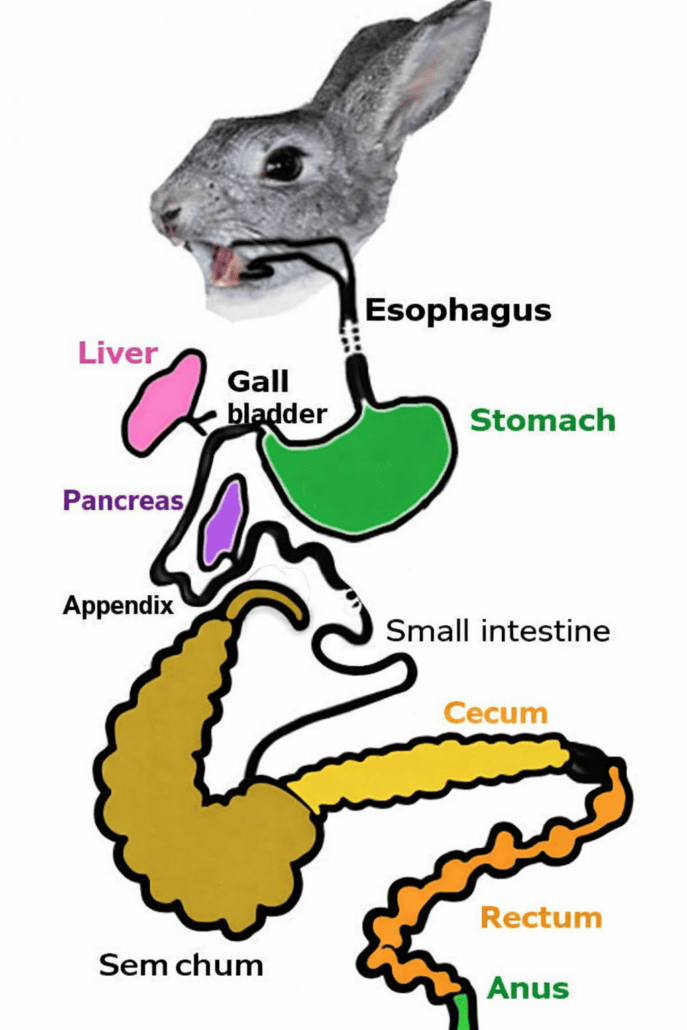

To understand why a rabbit requires a special diet and how dietary mistakes can affect it, it is important to become familiar with the process of digestion.

The task of digestion

All food that a rabbit consumes is, at first, a foreign substance to the rabbit’s body. The nutrients cannot be absorbed or utilized in this form.

The task of digestion is therefore to break the food down into its smallest building blocks so that these can then be absorbed through the intestinal wall. After that, metabolism begins, meaning the blood transports the absorbed substances to the individual organs.

Only some vitamins, water, minerals, and hormones can bypass actual digestion and be absorbed through the intestinal wall without being transformed. All other substances (carbohydrates, fats, proteins, etc.) must first be digested.

Individual stages of digestion…

In the mouth

Rabbits take in food using their incisors, lips, and tongue, and then grind it with the chewing movements of the molars (lower jaw) (see tooth wear). This mechanical breakdown is important so that the food pulp can pass through the esophagus and so that enzymes can act optimally (larger surface area).

Saliva plays a special role here: it mixes with the food and allows it to be swallowed easily. In addition, it begins to dissolve the food pulp and prepares it for further digestion, especially through enzymes that break down carbohydrates. Of particular importance is the starch-splitting enzyme amylase, which breaks starch down into sugar.

Rabbits produce an amount of saliva each day equal to about 10% of their body weight.

Dental diseases

Depending on the type of food, a rabbit’s teeth are subjected to different levels of wear. The more the rabbit has to chew in order to meet its energy needs, the better the teeth are naturally worn down. Energy-rich feeds (dry food, grains, etc.) and already ground feeds (pellets, extruded feeds, recovery mashes) require very little chewing and are swallowed quickly.

For this reason, even so-called “high-fiber pellets” are not suitable for proper tooth wear, because they consist of ground ingredients. In contrast, fibrous foods such as grasses, herbs, hay, and fresh greens must be chewed for a long time.

The diet should also not be excessively high in energy, so that the rabbit has to consume larger amounts to feel full, which increases chewing activity. This ensures optimal and natural tooth wear.

Special characteristic

Unlike humans, rabbits are hardly able to burp or vomit. This is because the junction between the esophagus and the stomach is tightly closed, and the weak peristalsis (muscular movement) of the stomach is mainly located at the stomach outlet. Anything that enters the stomach can only be transported further downward. Burping or vomiting is therefore almost impossible.

For this reason, rabbits do not need to be fasted before surgery, as there is no risk of choking due to vomiting. Another reason lies in the rabbit’s natural feeding behavior, to which its digestive system is perfectly adapted. Rabbits eat small amounts of food repeatedly during their active periods instead of consuming a few large meals. Their stomach is therefore designed for a continuous intake of food.

“Fasting” in the usual sense would also be pointless, because the stomach is never completely emptied; food residues always remain. Unlike in other animals, a rabbit’s stomach is therefore never truly empty.

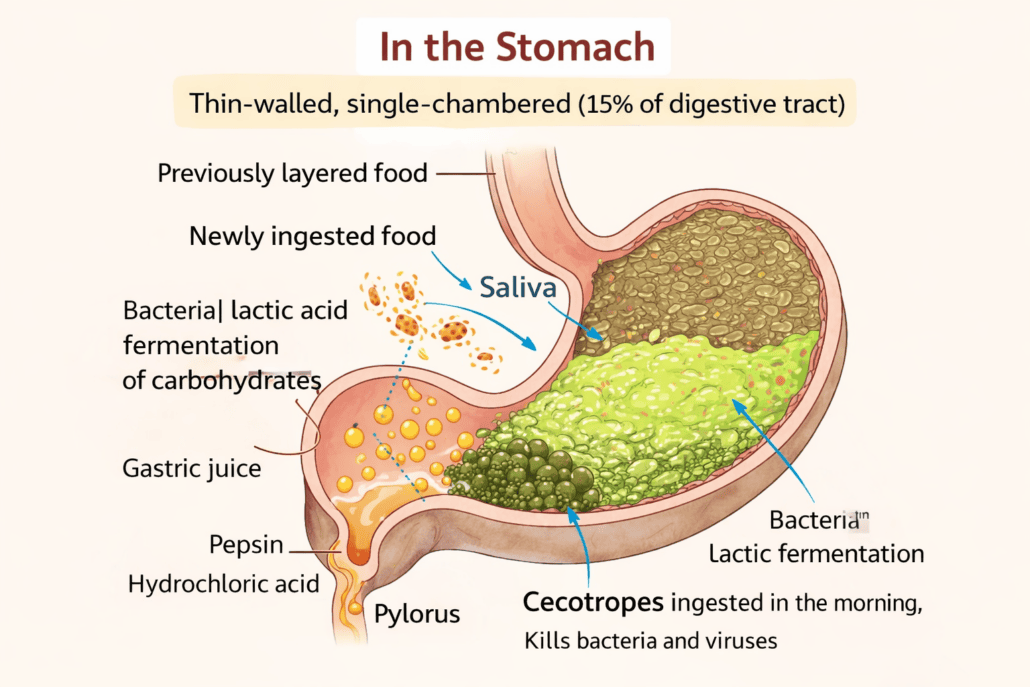

In the stomach

After swallowing, the food pulp passes through the esophagus into the thin-walled, single-chambered stomach (which makes up about 15% of the digestive tract). It is important to note that the previously layered food remains in place, while newly ingested food usually settles in the center. Rabbits always retain a certain amount of food in the stomach, so it is never completely emptied. One advantage of this is that newly ingested food is always mixed with existing contents, which allows potential toxins to be more strongly diluted.

The swallowed saliva continues to act enzymatically on starch, breaking it down. This is followed by bacterial lactic acid fermentation of carbohydrates. Gastric juice consists of hydrochloric acid and the protein-splitting enzyme pepsin and is produced by the gastric mucosa. Depending on the type of food consumed, its acidity and hydrochloric acid concentration vary. The hydrochloric acid, depending on the pH value, kills many bacteria and most viruses.

In young animals, however, gastric acidification is much weaker. As a result, bacteria and viruses can pass through the stomach more easily at this age and colonize the rest of the digestive tract. During the ingestion of cecotropes (which usually occurs in the morning), the stomach is also only mildly acidified.

Gastric acid prevents fermentation and permeates the food pulp. Only when the contents are sufficiently moistened does the pylorus open, allowing the chyme to be released into the small intestine in small portions.

Special characteristic

Rabbits rely on a continuous supply of digesta in the stomach; their digestive process must remain constantly active. However, contrary to common belief, this does not mean that they must eat continuously (so-called “permanent feeding,” often described as “in at the top, out at the bottom,” the “garden hose principle,” or a constantly overfilled stomach and intestines). Rabbits are well able to bridge short fasting periods by consuming cecotropes.

Only after approximately 12 hours without any food intake do they reach a critical state. Because rabbits follow a fixed rhythm of cecotrope production and hard-feces excretion, it is nevertheless essential that food is available at all times, allowing them to regulate their intake themselves in accordance with their natural digestive rhythm.

Gastrointestinal diseases

Rabbits are extremely sensitive. Feeding errors, parasites, or refusal to eat (for example due to pain or other illnesses) can quickly become life-threatening. Digestion can come to a halt when the food mass dries out; as a result, gas builds up. The animal becomes apathetic and stops eating. At this point, the stomach is filled with more food and gas than its volume can accommodate. A rabbit’s stomach is not very elastic and its stomach and intestinal walls are very thin, so severe overfilling and gas accumulation can even lead to ruptures of the stomach wall. Gastric overfilling and bloating are most commonly caused by refusal to eat (dental disease, pain, etc.) or by unsuitable, strongly swelling feed.

Gastric dilation

Gastric dilation is the most common disorder of the digestive tract. It develops as a result of food refusal. Rabbits may stop eating for many reasons: because they cannot eat (diseases of the teeth, mouth, or jaw), because they do not want to eat (pain caused by “hidden” diseases such as uterine disorders), or because of nausea (e.g. kidney failure, liver disease). Careful diagnostics are therefore life-saving. In only very rare cases are hairballs the sole cause. In most cases, the problem is thickened, dried food mass, which may contain some hair but mainly consists of feed material. Affected animals require intensive veterinary treatment, and the underlying cause must be identified and corrected.

Constipation, obstipation, hairballs

True hairballs are relatively rare and are often confused with gastric dilation. However, they do occur. A severely slowed or completely stopped intestinal transit, resulting in absence of feces, can have various causes. Among the most common are ingestion of clumping cat litter, straw pellets, feed pellets, or other materials that swell or clump strongly in the stomach and intestines (foreign bodies, vetbed fibers, carpet fibers, etc.). Large amounts of ingested fur (from self-grooming, nest building, grooming of other rabbits during molting, or pathological fur pulling) can also knot together in the intestine to form firm masses (hairballs) and cause obstruction.

Constipation is strongly promoted, or even triggered, by a very dry diet and/or lack of free access to drinking water. Dry food pulp cannot be sufficiently moistened and therefore does not move on. Natural rabbit food consists of about 70–80% water, and the digestive system is adapted to transporting very moist contents. Lack of exercise, housing that restricts movement, and obesity can further aggravate constipation. In general, a low-fiber, dry diet markedly increases the risk of obstipation in rabbits.

Gastric overloading

Feed pellets, mixed feeds, grains, extrudates, dried vegetables, and even bedding pellets (especially straw pellets, which are readily eaten) – in fact, almost all dry feeds – swell when they come into contact with liquid. If a rabbit greedily fills its stomach with dry food, a dry mass forms that cannot be transported onward. In the stomach, the food is soaked with gastric juice, which contains hydrochloric acid, so that it becomes suitable for further passage. Because this fluid causes dry feed to swell, its volume increases significantly. Most pellets (including grain-free pellets) expand to three to five times their original volume in soaking tests. Since the stomach cannot expand three to fivefold, pathological overfilling and even rupture of the stomach wall can occur.

The pylorus allows passage only when the food is sufficiently moistened and swollen by gastric juice. Dry food is not transported onward. The stomach therefore becomes massively overloaded. Non-swelling and moist foods do not cause this problem unless they are fed together with swelling dry feeds (even if given at different times), because their high water content can further intensify the swelling process.

Periods of hunger, irregular feeding, and fluctuating food availability also promote gastric overloading. Hungry rabbits may gorge on suddenly available or particularly palatable food and fill the stomach so excessively that even slight further expansion places dangerous strain on it. Rabbits prone to gastric overloading should therefore be fed at least twice daily in such quantities that no fasting periods occur and the same food is available around the clock. An ad libitum feeding regime is ideal.

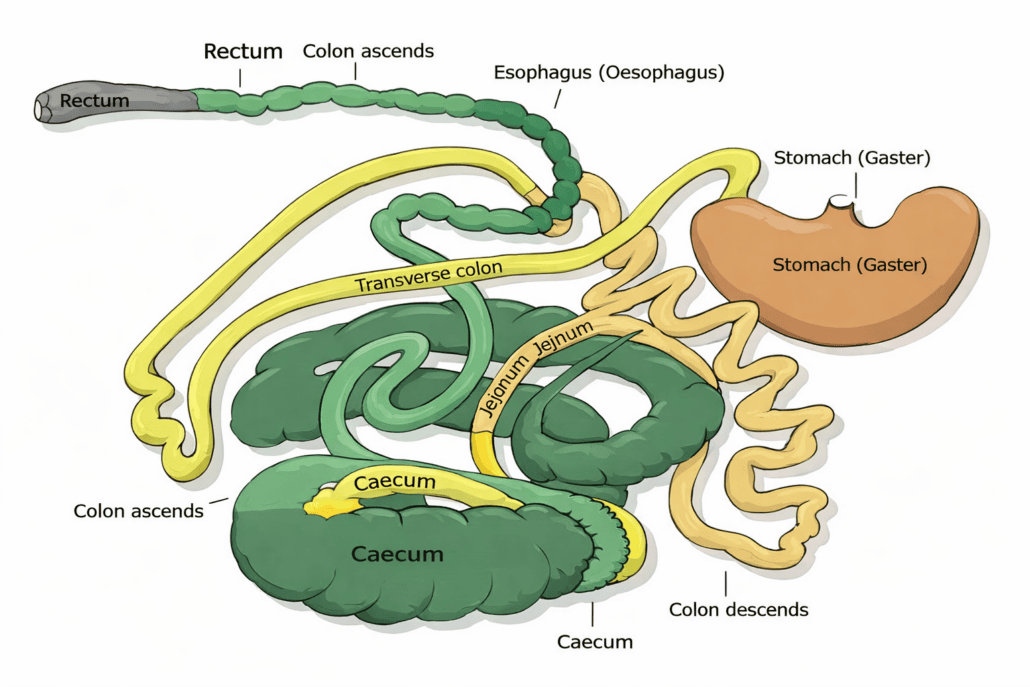

In the small intestine (duodenum, jejunum, ileum)

In the small intestine, nutrients are broken down into their individual building blocks with the help of enzymes secreted by the pancreas and bile from the liver: fats into glycerol and fatty acids, proteins into individual amino acids, and carbohydrates into simple sugars. Only these smallest components can be absorbed through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream.

The first section of the small intestine is the duodenum. Here, strongly alkaline secretions (pancreatic juice and bile) neutralize the highly acidic stomach contents so that the digestive enzymes can act effectively, breaking down proteins and carbohydrates and allowing the resulting nutrients to be absorbed through the intestinal wall into the blood.

In the jejunum, the body absorbs minerals, extracts vitamins from the intestinal contents, and, through further enzymatic activity, continues the digestion of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins so that they can be taken up through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream. If these substances are not broken down, they cannot be absorbed.

The absorbed nutrients are transported via the portal vein system to the liver, where they are processed and converted into forms that can be utilized by the rabbit’s body.

Worms and other intestinal parasites & secondary diseases caused by toxins in the body

If food intake is too rapid (gorging), the food pulp passes too quickly into the small intestine and is insufficiently neutralized in the duodenum, so that it continues in an acidic state. As a result, the digestive enzymes cannot function properly, because they require a neutral to alkaline environment. This leads to fermentation and putrefaction and to inadequate nutrient absorption.

As a protective response, the body produces mucus (from glycoproteins) to neutralize the acidic contents. However, this mucus is not eliminated and, especially in chronic cases (when overly acidic chyme repeatedly enters the small intestine), it persists. Layer upon layer of mucus then accumulates in the small intestine.

Large numbers of bacteria, parasites, fecal concretions, and worms settle in this mucus, where they find ideal living conditions. These parasites feed on the intestinal contents and, through fermentation and putrefaction, produce various toxins. These toxins are absorbed via the portal vein system and transported to the liver.

The result is a gradual intoxication of the entire body. The toxins spread to all organs and tissues, potentially leading to disorders such as diseases of the brain, skin, and other systems.

Diarrhea

When a rabbit passes mushy or watery feces, this is referred to as diarrhea. It is caused by irritation of the intestinal lining and, in later stages, by inflammation of the intestinal mucosa. In rabbits, the intestinal lining becomes inflamed very quickly, for example due to heavy strain from an improper diet (such as dry food, grains, sweets, treats), toxic substances that damage the mucosa, infections, or digestive disturbances (gas, parasites, imbalanced intestinal flora, increased amounts of poorly chewed food due to dental problems, etc.).

In the large intestine (cecum, colon, rectum)

Colon separation mechanism:

Unlike in most herbivorous animals, not all food particles enter the cecum in rabbits. While the coarse fiber of the food pulp is transported further into the colon, the fine particles are directed into the cecum. This process is called the colon separation mechanism and takes place in the first section of the large intestine.

While movements of the cecum push the coarse fibers onward into the colon, the peristalsis of the colon washes fluid and fine particles (< 0.3–0.5 mm) back into the cecum.

The cecum makes up about 43% of the digestive tract and differs from the other digestive sections because no digestive enzymes act there. This allows the rabbit to utilize food components that could not be broken down enzymatically in the small intestine.

The cecum is a large fermentation chamber in which, through controlled microbial fermentation (similar to but less efficient than in ruminants), mainly the previously indigestible fine particles are digested. During this process, volatile fatty acids are produced, which enter the metabolism, as well as proteins, sugars, B and K vitamins, ammonia, and urea. The volatile fatty acids alone can cover about one third of the rabbit’s energy requirements.

The remaining products cannot be absorbed in the cecum. Therefore, during cecotrophy (cecal feces phase), the rabbit excretes them and immediately takes them directly from the anus with its mouth and swallows them. Because cecotropes consist only of fine particles, they have a soft, unstructured consistency and form a uniform mass when crushed.

Cecotropes are coated with a protective mucus layer (mucin), which protects them in the remaining intestinal tract and, after re-ingestion, in the stomach. They then reach the small intestine, where they are digested. In this way, the rabbit absorbs proteins, sugars, and vitamins.

If cecotropes are not taken up directly, they are usually found as grape-like clusters or, when crushed, as soft, pasty or watery, sticky masses.

At a different time, hard feces are formed in the large intestine from the coarse particles of the digesta. These are shaped by muscular movements along the intestinal tract and are finally excreted.

Special characteristic

Because of the special importance of cecal digestion in rabbits and the associated separation of small particles (particles < 0.3–0.5 mm are transported into the cecum) from large, indigestible structural fibers (which are excreted), rabbits are particularly dependent on long fibers (> 0.5 mm) to maintain normal digestive activity.

Ground or very dusty feed therefore mainly enters the cecum, which can lead to overfilling of the cecum and insufficient filling of the colon. However, adequate filling of the colon with coarse food particles is vital, as this is what keeps intestinal motility and digestion going.

Finely ground feeds such as pellets and extrudates (the colorful dry feed rings and chunks made from ground meal), dusty hay, liquid recovery diets, or feeds low in indigestible fiber can therefore greatly slow down digestion or even bring it to a standstill. For this reason, such feeds are unsuitable as a primary diet for rabbits.

Special characteristic

Because rabbits rely on bacterial fermentation in the cecum, they are particularly sensitive to the administration of antibiotics. While the other sections of the digestive tract function similarly to those of other mammals and are largely unaffected by antibiotics (since enzymes and bile are not influenced by them), the cecum is populated by bacteria—the intestinal flora—which can be destroyed by antibiotics.

In rabbits, cecal fermentation is essential for obtaining energy and vitamins from the diet. If this bacterial flora is killed or disturbed, it can lead to abnormal fermentation, gas formation, diarrhea, and other digestive disorders. Oral administration of antibiotics in particular has a strong impact on the cecal flora.

For this reason, subcutaneous administration (injection) is generally preferred in rabbits, as it interferes much less with the cecal microflora.

Gas, tympany, bloat

When a rabbit’s stomach or intestines fill with gas, this indicates a dysfunction of digestion that always has underlying causes. One possible cause is a diet change that is too abrupt or feeding large amounts of unfamiliar food. The gastrointestinal flora is always optimally adapted to the usual diet and changes when the diet changes (for example in wild rabbits when winter begins and their food differs from summer). To allow this adaptation so that new food can also be digested properly, it must be introduced gradually. Otherwise, it remains undigested in the digestive tract because the appropriate microorganisms are not yet present to process it.

Fermented, unsuitable, moldy, or heavily pesticide-contaminated food can also trigger gas formation. Another common cause is a diseased digestive tract that struggles to break down food because it has been severely stressed by improper nutrition. This occurs especially with fundamentally incorrect feeding that damages the digestive system due to its unnatural composition and unsuitable ingredients (for example, dry commercial feeds). A compromised digestive tract is then quickly overwhelmed and cannot properly digest food; individual components begin to ferment. In such cases, yeasts, coccidia, E. coli bacteria, or intestinal inflammation are often detected. Intestinal infections and parasites can further impair digestion and promote gas formation. Frequently, the intestinal flora is also incomplete or imbalanced after antibiotic treatment.

Dental problems (which are likewise often caused by improper diet) aggravate this process, as insufficiently chewed food enters the digestive tract and places additional strain on it.

If digestion comes to a standstill (for example due to constipation, toxins affecting intestinal motility, loss of appetite, or lack of food), the food that remains too long in the stomach or intestines can begin to ferment, again leading to gas accumulation. In particular, a diet that is too dry and too energy-dense is one of the most common causes of tympany. Commercial dry feeds (including “grain-free” dry feeds), dried vegetables, and other dry foods slow digestion because they make the rabbit feel full quickly (high energy density and strong swelling capacity—the food pulp swells on contact with gastric acid and can increase severalfold in volume). This dry food fills the stomach, partially dehydrates the contents, and leads to very slow passage or even gastric stasis.

Because the rabbit then eats little or nothing (it feels full and overfilled), no fresh food pushes the contents onward, and the pylorus often remains closed, as it only opens when the stomach contents are sufficiently moist. Food that remains stagnant is extremely dangerous, because fermentation produces gases that cannot be transported further (rabbits cannot burp), so the stomach can rapidly distend with gas. The intestines can become similarly affected and distend as well. Even when a rabbit stops eating entirely, gas can still develop because the existing stomach and intestinal contents remain in place and begin to ferment, which often occurs in severely ill animals.

Lack of movement can worsen gas accumulation. Rabbits with bloating benefit from moving as much as possible, as activity stimulates intestinal motility and helps restore normal digestion.