By far the most common parasite affecting rabbits is the threadworm (Passalurus ambiguus), but other roundworm infections, such as stomach worm infestations (Graphidium strigosum), Trichostrongylus retortaeformis, Strongyloides spp., and Trichuris leporis, can also occur. Very rarely, rabbits can be affected by tapeworms (Cittoteania, Mosgovoyia, and Ctenotaenia), flukes/trematodes (Fasciola hepatica/Dicrocoelium dendriticum), and lungworms (Metastrongylus, Protostrongylus).

Contents

Diagnosis: How do I recognize a worm infestation?

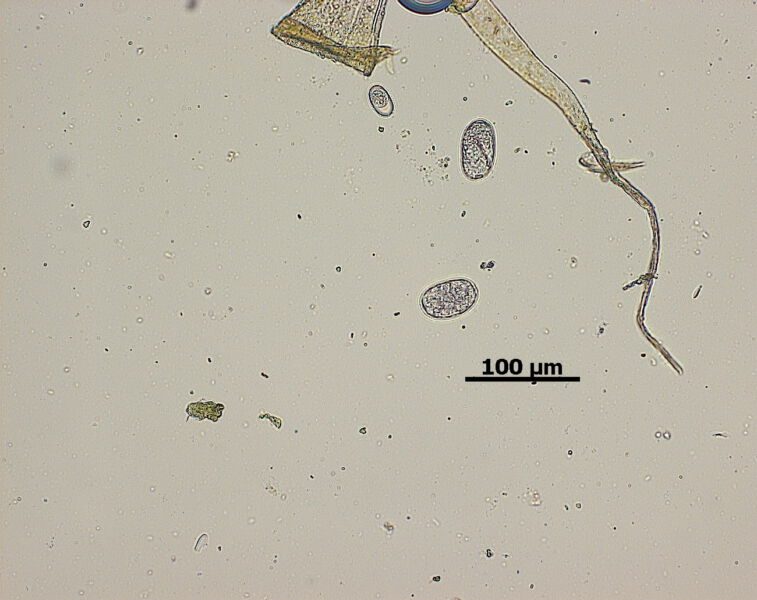

A worm infestation is diagnosed through a fecal sample collected over at least three days, as worms are shed cyclically. A worm infestation is often detected during routine fecal examinations (worm eggs or worms), as many rabbits show no symptoms. Whole worms are only expelled in cases of heavy infestations; if you show these to your vet, treatment can begin immediately without a fecal sample.

An annual „parasite check“ is very important for rabbits to detect parasites early and to ensure that vaccinations are effective, as a heavy worm infestation can interfere with their effectiveness. The samples can either be submitted at the veterinary clinic if they offer this service or sent directly to a laboratory. In the lab, the feces are examined using a flotation method, and a collection of feces from three days is required. Additionally, to rule out a worm infestation more reliably, a tape test of the anal region should be performed. Unfortunately, there are often fecal samples that do not contain eggs or worms even when the rabbits are affected. The most common worm, Passalurus ambiguus, is not always detectable in fecal samples; a more reliable diagnosis is made by combining a fecal sample with a tape test from the anus.

Note on lungworms (in case of respiratory symptoms): For the very rare small lungworms, the migration method can be used to detect larvae in the feces.

Note on liver flukes (in case of liver disease): For the very rare liver flukes, the sedimentation method is suitable for detection.

Practice Tip:

For submission, a sample of a few feces from three consecutive days is enough, placed in a fecal collection tube. For the tape test, simply stick a piece of tape over the anus, press it gently, then peel it off and stick it onto a microscope slide. Fecal collection tubes and microscope slides are available at the pharmacy.

Causes & Transmission

Rabbits typically become infected by consuming food contaminated with worm eggs (wild plants or purchased vegetables) or through grooming themselves. Additionally, infected rabbits contaminate their living environment with the parasitic stages present in their feces, which can lead to reinfection (re-infection) if the environment is not properly cleaned. Once a rabbit is infected, it may continue to reinfect itself, especially when ingesting cecotropes. Very healthy rabbits with intact immune systems may not show visible symptoms of a worm infection, but they are continuous shedders of worm eggs, thus posing a risk to weakened animals in contact with them.

Factors that Favor Worm Infestation:

- Collecting greens from fields frequented by wild rabbits or hares. Washing fresh food under running water to prevent worm infestations (especially for the prevention of tapeworms).

- Contact with rabbits that shed worms.

- An unhealthy diet that is not based on fresh food (especially greens).

- A one-sided or overly cautious diet (rabbits need many secondary plant compounds).

- A compromised gut flora, for example, due to medication, anesthesia, early separation from the mother, hereditary diseases, etc.

- Inadequate hygiene in the rabbit’s enclosure, feeding from the floor (food contact with feces), as worms also go through developmental stages outside the body and can be ingested through contaminated food.

- Overgrazed or muddy areas (solid enclosures with dirt floors, small meadow runs, many rabbits in a small space, lack of pasture rotation…).

- Stress, such as from moving, disharmonious groups, pairing, frequent handling, limited space (cage/pen housing), or a rabbit living alone.

- Rain and moisture (especially below 10°C) without adequate weather protection.

- Other diseases that weaken the rabbit (think of Megacolon syndrome!): Heavily infested animals almost always have an underlying condition!

Symptoms – How Does Worm Infestation Manifest?

Worms feed on the food bolus in the digestive system, which can lead to nutrient deficiencies and weight loss in rabbits when infested. This is especially detrimental during growth; young rabbits are more likely to suffer from worm infestations. However, a worm infection can also become visible through digestive issues. Symptoms may include diarrhea, bloating, constipation, loss of appetite, weight loss, and a generally poor condition, often accompanied by dull fur or a significant molt. In cases of chronic worm infestations, the animals may develop intestinal inflammation, which further stresses them and may require additional treatments.

Different Types of Worms

The following worms are common in rabbits:

- Threadworms/Pinworms/Oxyurids (Passalurus ambiguus):

The so-called Passalurosis is the most common worm disease in rabbits and occurs worldwide, both in domestic and wild rabbits. It is caused by Oxyurids, with Passalurus ambiguus being relevant for domestic rabbits. These worms do not pose a threat to humans (not zoonotic), unlike Oxyurids from rodents. Passalurus ambiguus lays its eggs around the anus, and diagnosis can be made more reliably with a Tesa tape smear in addition to a fecal examination.

- Stomach Worm Infestation (Graphidiosis):

The reddish stomach worm (Graphidium strigosum) is rare in pet rabbits but can occur more frequently in outdoor rabbits, especially if wild rabbits have access to the enclosure or if the rabbits are grazing on wild rabbit-infested meadows. These worms primarily affect the stomach, though they may also be found in the small intestine.

- Whipworms (Trichuris leporis):

Whipworm eggs require high moisture content to develop, so they are more likely to occur in moist, shady enclosures with natural soil or in meadows with similar conditions.

- Trichostrongyloidiasis (Trichostrongylus retortaeformis):

Similar to stomach worms, Trichostrongyloids primarily affect wild rabbits and are rarely seen in domestic rabbits. They parasitize in the small intestine and develop directly without an intermediate host. The eggs are shed in the feces and contaminate the environment. Infection occurs when rabbits ingest contaminated food.

- Tapeworm Infestation in Domestic Rabbits:

Tapeworm infestations are very rare in domestic rabbits but can occur worldwide. Wild rabbits are more often affected, but tapeworms are still rare in them as well. The worms use mites (such as moss mites or horn mites) as intermediate hosts, which rabbits must ingest orally with contaminated food. Three genera can parasitize rabbits: Cittoteania, Mosgovoyia, and Ctenotaenia.

- Liver Fluke Infestation in Rabbits:

Liver flukes (Trematodes) are extremely rare in domestic rabbits, often having little significance. However, infections with Fasciola hepatica (large liver fluke) or Dicrocoelium dendriticum (small liver fluke) are still possible. The large liver fluke typically parasitizes sheep and goats but can also infect other mammals, including humans. Prevention involves avoiding food from damp or marshy areas (for large liver flukes) or from sheep pastures (for small liver flukes). These worms have a very short life cycle, with adult worms developing in just five days. In cases of severe infestation, symptoms may include mucous to watery diarrhea, lethargy, weight loss, and even death. Infection can occur through contaminated food or ants. Infected rabbits may show liver-related symptoms, including poor appetite, weight loss, jaundice, and edema. The small liver fluke is harder to detect as it does not produce visible symptoms. Chronic infections may show fluke eggs in sedimentation tests.

- Lungworms (Metastrongylus, Protostrongylus):

Lungworms are extremely rare in rabbits but can cause persistent and severe respiratory issues (sneezing, coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, head shaking during breathing), weight loss, increased thirst, weakness, and occasionally neurological symptoms. Infection occurs when rabbits ingest infected snails or come into contact with infected snail slime. This is typically a risk in meadows grazed by sheep or goats. The „migration test“ is used to detect larvae in the feces.

- Tapeworms from Carnivores and Their Cystic Forms (Cysticercus pisiformis of Taenia pisiformis & Coenurus serialis of Taenia serialis):

Rabbits can ingest tapeworm eggs from dogs, cats, and other carnivores and act as intermediate hosts. Typically, these cysts do not cause illness in rabbits. There is no risk of transmission to humans from infected rabbits. The cysts, known as Cysticercus pisiformis of Taenia pisiformis, can be found as small blisters in the liver, mesentery, or omentum. Coenurus serialis cysts of Taenia serialis are found in muscle or subcutaneous tissue and, in rare cases, behind the eye.

Treatment

There are various ways to treat worm infestations in rabbits, depending on the type of worm.

The most well-tolerated treatment, suitable for almost all types of worms (with exceptions such as tapeworms and liver flukes), is the use of Fenbendazole (Panacur® Pet Paste or Panacur Suspension, 20 mg/kg). Many rabbits will eat it voluntarily if mixed with oatmeal, baby food (apple-banana-oat flavor without yogurt), mashed banana, or another favorite food. The recommended treatment schedule is 5 – 5(-14) – 5 (5 days on, 5-14 days off, 5 days on). In many cases, a single 5-day course is sufficient.

Other commonly used medications include Febantel/Pyrantel (Welpan®, 10 mg/kg, for 1-5 days or 3-14-3) and Mebendazole (Telmin®, 20 mg/kg, for 3-5 days or 3(-5)-14-3(-5)), which are used primarily when Panacur® is ineffective or when resistance is present.

In some cases, treatment with Imidaclopridum and Moxidectinum (Advocate®, 0.1 ml/kg) may be helpful, as it works for up to four weeks and effectively prevents reinfection.

Some veterinarians may use Ivermectin (0.4 – 0.5 mg/kg once or multiple doses spaced 14 days apart). However, it is important to note that some worms are already resistant to this treatment.

If additional symptoms are present (e.g., diarrhea), they should, of course, be treated symptomatically.

Good hygiene is important during treatment:

- Litter boxes should be completely changed every 1-2 days to prevent reinfection.

- The rabbit’s enclosure should be thoroughly cleaned during the medication period.

- Disinfection is generally not necessary.

Tapeworms

- Praziquantel: Administered once at 10 mg/kg orally, with a repeat dose after 10-14 days.

- If necessary, provide supportive treatment for diarrhea.

- Hygiene of litter boxes is crucial: Completely remove and empty litter every 1-2 days. Additionally, the entire enclosure should be thoroughly cleaned.

Liver Flukes (Trematodes)

- Closantel: Administered once at 10 mg/kg orally, or Fasinex can be used as an alternative.

- Albendazole may also be considered as an alternative treatment.

- Support liver function, for example, through milk thistle extract (Mariendistelextrakt).

Prevention

There are some products and forage plants that alter the gut environment, making it more difficult for parasites to thrive. These substances might be useful either as a preventive measure or alongside veterinary treatment:

- Herbal extracts or mixtures: Example: AniForte WermiX.

- Neem leaf powder: The main active ingredient, Azadirachtin, mimics the insect hormone Ecdyson and acts as an antifeedant to inhibit larval development. Dosage: 25-50 mg/kg body weight, divided into several doses throughout the day.

- Products like DarmAktiv, RodiCare akut, Rodicolan, Colosan, or Herbi Colan may be useful as supplementary treatments.

- Preventive herbs: Several forage plants can help prevent or reduce worm infestations, such as thyme, wormwood, mugwort, tansy (can be used in larger quantities daily), watercress, common knotgrass, blueberries, garlic, spring onions, wild garlic, chives, leek (porree), pumpkin seeds, and many other wild, meadow, or kitchen herbs.

- Horseradish and ginger, when administered over a longer period, can significantly reduce worm infestations, particularly when used together. Studies on sheep and dogs support this approach. While these ingredients might not completely eradicate worms, they can reduce infestations and are valuable as a preventive measure, especially for rabbits prone to worm infections.

Prophylactic Worming Treatments?

The listed herbal products are great for preventing worm infestations.

However, a preventive worm treatment doesn’t make sense, as the effectiveness of the medications only lasts while they are administered. Medications like Panacur® and similar drugs should never be given preventively unless advised by a veterinarian. Treatment should only be administered after a poop sample is examined and confirms a worm infestation, or if worms are found in the poop that the medication targets.

Why?

Worm treatments do not have a preventive effect. This means that giving a worm treatment when the rabbit does not have worms will have no effect, and in the days following the treatment, the rabbit may become infected again, as the treatment does not prevent future infections.

Furthermore, the frequent use of these medications can lead to resistance, which has been observed in the past. This results in the need for increasingly intense treatments (longer durations and higher dosages), or existing medications may no longer be effective.

Rabbits can harbor various types of worms and other intestinal parasites (like coccidia, giardia), each of which requires a different medication. Without an examined poop sample, you can’t know which medication will work!

In countries like Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Italy, and the Netherlands, the preventive use of dewormers is prohibited. It’s required to prove the presence of worms before administering any chemical worm treatment.

Sources, including:

Csokai, J. (2018): Parasitologische Kotuntersuchung bei Kaninchen und Meerschweinchen. kleintier konkret, 21(S 02), 29-35.

ESCCAP (European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites) Deutschland e.V. https://www.esccap.de/empfehlung/heimtiere/ [abgerufen am 20.04.2024]

Bauer, V (2006). Parasitosen des Kaninchens. In: Boch J., Supperer R. Herausgeber: Schnieder, T. Veterinärmedizinische Parasitolige. 6. Auflage. Parey, Stuttgart. P. 561-575.

Baker D.G. (2007) Parasites of Laboratory Animals. Second Edition. American College of Laboratory Animal Medicine, Blackwell Publishing, New Dehli.

Beck W., Pantchev N. (2006) Praktische Parasitologie bei Heimtieren. Kleinsäuger. Vögel. Reptilien. Bienen. Schlütersche, Hannover.

Beck, W., Pantchev, N. (2009): „Magen-Darm-Parasiten beim Kaninchen–Erregerbiologie, Pathogenese, Klinik, Diagnose und Bekämpfung.“Kleintierpraxis 11.5 278-288.

Brendieck-Worm, C., & Melzig, M. F. (Eds.). (2018): Phytotherapie in der Tiermedizin. Georg Thieme Verlag.

Brendieck-Worm, C., Nadig, A., & Thoonsen, Y. (2018): Vom Umgang mit Parasiten. Zeitschrift für Ganzheitliche Tiermedizin, 32(03), 96-104.

Eckert J, Friedhoff KT, Zahner P, Deplazes P. (2008): Lehrbuch der Parasitologie für die Tiermedizin. 2. Aufl. Enke; Stuttgart

Ewringmann, A. (2009): Kotuntersuchung beim Kaninchen. Tierarzthelfer/in konkret, 5(02), 16-17.

Ewringmann, A. (2017): Leitsymptome beim Kaninchen: Diagnostischer Leitfaden und Therapie. Georg Thieme Verlag.

Hein, J. (2016): Durchfall beim Kaninchen–Ursachen und Therapie. kleintier konkret, 19(S 01), 2-9.

Hein, J. (2017): Durchfallerkrankungen bei Kleinsäugern: Ursache, Diagnostik, Therapie. Schlütersche

Kraft, W., Emmerich, I. U., & Hein, J. (2012): Dosierungsvorschläge für Arzneimittel bei Kleinnagern, Kaninchen und Frettchen. Schattauer Verlag.

Schmäschke R. (2013): Die koproskopische Diagnostik von Endoparasiten in der Veterinärmedizin. Schlütersche; Hannover

Schmäschke, R. (2014): Parasitologische Kotuntersuchung des Kaninchens. kleintier konkret, 17(S 01), 31-33.

Starkloff, A. 2010: Einfluss von Wetterfaktoren und sozialer Umwelt auf den Endoparasitenbefall juveniler Wildkaninchen (Oryctolagus cuniculus L.) Diss. University of Bayreuth

Zinke, J. (2004): Ganzheitliche Behandlung von Kaninchen und Meerschweinchen: Anatomie, Pathologie, Praxiserfahrungen; 14 Tabellen. Georg Thieme Verlag