Contents

Cystitis (bladder inflammation)

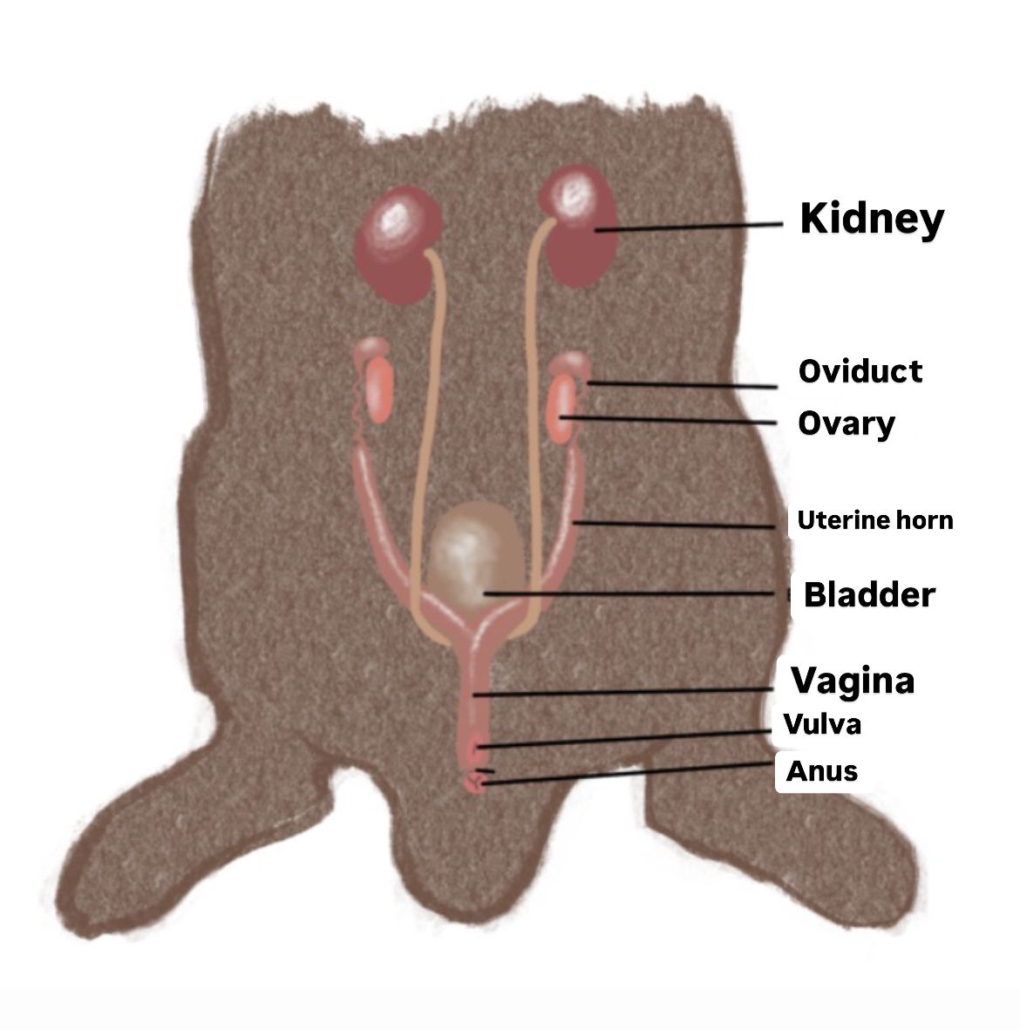

Bladder infections are not uncommon in rabbits, especially due to diarrhea or urinary grit and bladder stones, which often lead to cystitis. Female rabbits are significantly more likely to develop this condition than males.

Warning! Wet fur poses a severe risk of flystrike (infestation by fly larvae)! Protect your rabbit!

Symptoms:

Usually, only a few of the signs listed below are displayed, such as the rabbit being simply lethargic, eating less, and urinating randomly in the enclosure.

- Difficulty urinating, raising the hindquarters, and staying in this position.

- Increased frequency of urination.

- Incontinence/poor hygiene (urine stains where the rabbit walks or stands, sometimes also droplets).

- Urine-soaked fur around the hindquarters, urinating on itself, sometimes leading to skin inflammation.

- Apathy (withdrawal, less participation in everyday activities).

- Decreased food intake due to pain.

- Some rabbits may become aggressive due to persistent pain.

Diagnosis:

- Palpation: Typically, a small, painful bladder can be felt.

- Urine test strips: Low pH (< 7), the presence of erythrocytes and hemoglobin, and sometimes nitrites may be detectable. Leukocytes are not reliable indicators in rabbits! (e.g., Combur test strips).

However, even with other values, bladder inflammation is still possible.

Urine strip evaluation:

- pH value: In healthy rabbits, a pH of 8-9 is normal. A decreased pH indicates a bacterial bladder or kidney infection, or metabolic imbalance (e.g., ketoacidosis).

- Erythrocytes: Positive for blood (bladder or uterine diseases), but blood can also be introduced during urine collection (spontaneous urine is typically blood-free; expressing the bladder: 1+ to 4+; cystocentesis and catheterization: usually 1+).

- Protein: Negative in healthy rabbits. A positive result could indicate a variety of conditions, such as urinary tract issues, kidney diseases, heart disease (including thymomas), shock, etc.

- Nitrites: Negative in healthy rabbits. A positive result suggests urinary tract infections, although false positives can occur due to contamination (bacteria) or nitrate-rich food.

- Bilirubin: Negative in healthy rabbits. Positive values often indicate liver coccidiosis.

Leukocytes: Not a reliable indicator in rabbits.

Urine: Often cloudy or mucous.

- Bacteriological examination of the urine (however, only urine obtained from bladder puncture should be used! Voided or spontaneously passed urine is almost always contaminated with bacteria).

- Exclusion of urinary grit and bladder stones through X-ray/ultrasound (these are usually associated with bladder infections). On ultrasound, the bladder wall appears thickened and rough.

Causes

- Initially, a cold may be suspected, but this is very rare in rabbits.

- Gastrointestinal diseases are a common cause.

- Urinary bladder sludge or bladder stones can cause damage to the bladder’s mucosal lining, leading to (often chronic) bladder infections.

Treatment

- The first priority is to identify and treat the underlying cause (X-ray, ultrasound, etc.)—whether it’s bladder sludge, bladder stones, or diarrhea.

- Bladder and kidney infections are treated by the veterinarian with antibiotics, ideally based on an antibiogram (refer to the bacteriological examination above).

- Infusions: A complete electrolyte solution (e.g., Ringer’s lactate, Sterofundin), or NaCl if sodium levels are very low and potassium levels are too high. Administer 80-100 ml/kg intravenously once daily or 40 ml/kg subcutaneously twice daily, reducing frequency once stabilized. Infusion sets and yellow 20G needles or butterfly needles are needed for this.

- Pain relief is crucial; Novalgin or Metacam are commonly used.

- For chronic or mild bladder infections, Angocin may be given (approximately 12 tablets per day, dissolve the protective coating; rabbits often eat them willingly, or they can be dissolved and administered with a 1 ml syringe). This treatment is also recommended if you wish to avoid antibiotics, for example, if another condition is already being treated.

- Other suitable treatments include Solidago Steiner Tablets, Eurologist, Uroplex, RodiCare Uro, or Harnwegemix (cdVet).

- Good litter hygiene is essential.

- An optional heat source may be provided.

- Ensure high fluid intake (provide multiple water bowls, as rabbits tend to drink less from bottles). Offer diluted fruit and vegetable juices without added sugar, and bladder and kidney teas can be beneficial. A fresh food diet is optimal for supporting the rabbit, as it helps flush the bladder similarly to an infusion.

- The underlying causes of such infections are often stones or grit, and they must be treated to prevent recurring infections.

- If the rabbit refuses food, it should be force-fed.

Sources, among others:

Angeli, C. (2008): Sonographische Untersuchung der abdominalen Organe beim Kaninchen (Doctoral dissertation, lmu).

Ewringmann, A. (2016): Leitsymptome beim Kaninchen: diagnostischer Leitfaden und Therapie, Georg Thieme Verlag.

Fuchs, S., Eberhardt, F., Niesterok, C., & Kiefer, I. (2013): Ultraschall bei Kaninchen und Meerschweinchen–Die häufigsten pathologischen Befunde des Harntrakts. kleintier konkret, 16(02), 8-14.

Glöckner, B. (2015): Nierenerkrankungen beim Kaninchen–Ursachen und Therapiemöglichkeiten. kleintier konkret, 18(S 02), 3-10.

Hein (2015): Urinuntersuchung beim Kleinsäuger – so einfach und doch so aussagekräftig. kleintier konkret 2015; 18(S 01): 30-35

Langenecker, M., Clauss, M., Hassig, M., & Hatt, J. M. (2009): Vergleichende Untersuchung zur Krankheitsverteilung bei Kaninchen, Meerschweinchen, Ratten und Frettchen. Tieraerztliche Praxis. Ausgabe G, Grosstiere/Nutztiere, 37(5), 326.

Nastarowitz-Bien, C. (2008): Sonographische Untersuchung des Abdomens bei Kaninchen (Doctoral dissertation, Freie Universität Berlin).

Rappold, S. (2001): Vergleichende Untersuchungen zur Urolithiasis bei Kaninchen und Meerschweinchen. Klinik für kleine Haustiere. Tierärztliche Hochschule Hannover, Hannover, 1-141.

Weiß, M. C. (2008): Harnuntersuchung beim Kaninchen. Tierarzthelfer/in konkret, 4(01), 8-9.

Zinke, J. (2004): Ganzheitliche Behandlung von Kaninchen und Meerschweinchen: Anatomie, Pathologie, Praxiserfahrungen; 14 Tabellen. Georg Thieme Verlag.