Contents

Coccidiosis (infection with coccidia), Eimeriosis

Coccidiosis is the most common parasitic disease in rabbits. It can cause significant losses, particularly in young rabbits at weaning age, although (weakened) adult rabbits can also be affected.

Coccidia are single-celled parasites that colonize the gastrointestinal tract of rabbits. They reproduce there and, as part of their life cycle, damage the intestinal tract. Rabbits are hosts to numerous species of coccidia, all of which belong to the genus Eimeria. Unfortunately, these parasites are widespread both in breeding facilities and in private rabbit ownership.

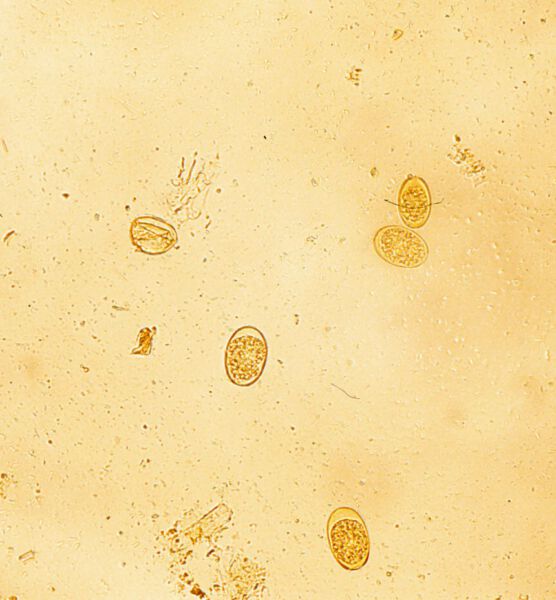

Eimeria flavescens unsporulated oocysts in the feces of a rabbit. Photo: Dr. M. Hallinger, exomed

Species

Many species of coccidia from the genus Eimeria have been identified in rabbits, including:

Eimeria stiedai, Eimeria magna, Eimeria perforans, Eimeria media, Eimeria irresidua, Eimeria piriformis, Eimeria coecicola, Eimeria elongata, Eimeria intestinalis, Eimeria matsubayashii, Eimeria nagpurensis, and others.

Coccidia differ in their pathogenicity, which depends on their reproductive cycles in the intestine (referred to as merogony). Certain species, such as Eimeria flavescens and Eimeria intestinalis, which undergo multiple merogonies, may be more pathogenic than other species. Additionally, the development of clinically apparent coccidiosis depends on several factors. For example, the simultaneous presence of multiple coccidia species in a rabbit can damage different sections of the intestine. The severity of the infection also depends on the parasite load and whether secondary bacterial infections, such as with Escherichia coli strains or Clostridium spp., are present.

Mixed infections with different coccidia species are also commonly observed!

Causes

- Rabbits often become infected with intestinal coccidia as young kits, either through their mothers, in pet stores, or through contact with other rabbits, contaminated food, or contaminated ground (e.g., meadows used as a food source that are frequented by wild rabbits). Rabbits from mass breeding facilities, such as those found in pet stores or small animal markets, are particularly prone to infection.

- To prevent infestation, always have a poop sample from any new rabbit tested by a veterinarian or sent to a laboratory before introducing it to the group. Additionally, poop testing should be performed before every vaccination, if there is any suspicion of infection, and at least once a year. Severe coccidia infestations can reduce the effectiveness of vaccines.

- Stress can trigger rapid multiplication of coccidia, leading to outbreaks. Common stressors include introductions to new groups, conflicts in unharmonious groups, relocations, frequent handling, rough treatment, solitary confinement, limited space (such as being kept in cages or small hutches), trips to the vet, or changes in living conditions. Rabbits that were previously asymptomatic can suddenly show symptoms under stress.

- Diet also plays an important role. Imbalances in gut flora can occur if rabbits are not primarily fed fresh greens and are instead given dry food (such as pellets, mixed feeds, or large quantities of grains and seeds), treats, excessive amounts of root vegetables or fruit, or other inappropriate foods. A monotonous or overly cautious diet can promote coccidia, particularly when rabbits lack access to the diverse secondary plant compounds they need for good health. It’s important to note that toxicity levels often associated with certain plants for dogs, cats, horses, or humans do not necessarily apply to rabbits.

- Environmental factors are also significant. If the ground in outdoor enclosures is heavily contaminated (e.g., from overcrowded grazing areas, unhygienic substrates, or soil floors), the immune system may become overwhelmed, leading to outbreaks. Well-maintained grassy areas are less problematic, while muddy or excessively soiled areas should be avoided. Hygienic flooring, such as paving stones in fixed enclosures, and regular rotation of grazing areas are ideal.

- Wild rabbits can also transmit coccidia to domestic rabbits if they share access to the same grassy areas.

- Certain health conditions can make rabbits more susceptible to coccidia, such as megacolon syndrome.

Poor hygiene and infrequent cleaning can exacerbate the problem. To minimize the risk, avoid offering food directly on the ground where it might come into contact with feces (use hay racks), and clean water and food containers daily.

- A disrupted gut flora can create an ideal environment for coccidia to thrive. This disruption can be caused by factors such as medication, anesthesia, early separation from the mother, hereditary diseases, or stress.

- Other illnesses can weaken rabbits to the point that coccidia can proliferate uncontrollably.

- In young rabbits, outbreaks can sometimes occur spontaneously during growth but are especially common during weaning or after moving to a new home.

- A damp or humid environment, poor ventilation, wet bedding, or rainy weather can promote the development of coccidiosis. Rabbits should always have access to dry, sheltered areas and should not be exposed to prolonged damp conditions.

- Finally, plenty of exercise is crucial for maintaining healthy digestion and preventing coccidia.

Clinical Picture

In rabbits, two forms of coccidiosis are distinguished: liver coccidiosis and intestinal coccidiosis.

Liver Coccidiosis / Bile Duct Coccidiosis

This form is more accurately referred to as bile duct coccidiosis, as the parasites multiply in the bile ducts of the liver. The disease is caused by bile duct coccidia (Eimeria stiedai). The parasitic stages enter the intestine via the bile and are excreted in the poops. These so-called „oocysts“ that are excreted with the poops can remain infectious in the environment for several months under moist and warm conditions. Infection occurs through the oral intake of these stages from the environment (e.g., through contaminated food).

When rabbits are infected with these parasites, symptoms may include liver issues, diarrhea, and digestive disturbances. This form particularly affects older, adult rabbits. It specifically targets the liver (liver coccidiosis), causing swelling and inflammation of the bile ducts. Grayish-white, abscess-like lumps form in the liver. As mentioned, this form is more common in older rabbits and leads to ongoing weight loss, dull fur, poor general condition, and eventually a reduced appetite. Other symptoms are similar to those of other liver diseases, but liver coccidiosis should always be ruled out through a poop examination (since coccidia are not always excreted) and an ultrasound examination: More on liver diseases.

Rabbits from dubious origins often come with coccidia already present.

Intestinal Coccidiosis

In intestinal coccidiosis, the coccidia multiply in the intestinal wall, causing damage to the tissue. In particular, Eimeria flavescens and Eimeria intestinalis are considered the more pathogenic species. However, mixed infections with other types of coccidia that parasitize the intestine are also common. Affected rabbits often show signs of digestive issues, including watery or foul-smelling diarrhea, bloating, and loss of appetite. Death can occur, particularly in young rabbits.

Coccidiosis is the most common cause of death in young rabbits. Juveniles are more vulnerable to intestinal coccidia than adult rabbits due to their less developed immune systems. Therefore, breeding females and weaning rabbits should be tested for coccidia before pregnancy and weaning, and treated if necessary.

Intestinal coccidia can also be present without noticeable symptoms, especially if the rabbits have developed some level of immunity or if the infection is caused by less virulent species. Often, all rabbits in a group may be infected, but only a few, weakened individuals will show symptoms.

However, if the parasites multiply excessively or the rabbit is stressed or weakened, even adult rabbits can develop symptoms of coccidiosis.

Symptoms may include (recurrent) bloating, excessive gas, stomach distension, and less frequently diarrhea (often foul-smelling), an increase in unprocessed cecotropes, soft or mushy poops, weight loss, a bloated abdomen, poor food intake, and other digestive issues. Affected young rabbits often appear underweight or show poor or slow growth. In some cases, mass die-offs may occur in young rabbits.

In rare cases, coccidia may cause paralysis, discharge from the mouth or nose, fever, and seizures in rabbits. In advanced stages, the rabbit may stop eating or become apathetic. White, thickened patches may appear in the intestine.

An increased amount of cecal pellets left behind may be a sign of coccidia.

Diagnosis: How are Coccidia Detected?

Coccidia are detected through a poop sample (using the flotation method). Since coccidia are not always excreted consistently, the poop should be collected over at least two days, preferably three, before being examined. The sample can be tested by a veterinarian or sent directly to a laboratory.

It is advisable to have rabbits tested for parasites at least once a year, preferably before their vaccination appointment. Newly acquired rabbits should always be tested for intestinal parasites before being introduced to other animals.

After infection with coccidia, it takes about 5 to 10 days for them to become detectable in the feces, or 14 to 18 days for liver coccidia (Eimeria stiedai).

Treatment and Care Measures

Coccidia should not be taken lightly! Prompt veterinary treatment is crucial when dealing with coccidia. Untreated young rabbits can die rapidly from coccidiosis or its symptoms, and weakened or chronically ill adult rabbits often fall victim to it as well. In breeding, large-scale deaths of young rabbits due to coccidiosis are quite common.

Coccidia should be treated as soon as they are detected in the feces.

It is important that new arrivals, rabbits for sale, young rabbits, and breeding animals (before mating) are tested for coccidia using a fecal sample, particularly in private rabbit keeping, so that the vaccination can optimally protect the rabbit.

The veterinarian will prescribe a medication to treat the coccidia (as detailed below). Not all rabbits in the group need to be treated, only those with an active infection. The veterinarian will provide specific recommendations. Make sure the medication is administered directly, as treatments given through drinking water or food are often inaccurately dosed (since one rabbit may drink more than another).

Common Active Ingredients Used for Treatment:

- Toltrazuril (Baycox®, 10-15 mg/kg > 0.2-0.3 ml/kg): This is a widely used treatment, but some rabbits may refuse food or have poor appetite after administration. Only the 5% white solution is suitable for rabbits; the 2.5% (clear) solution is intended for poultry and is not suitable for rabbits, as it can cause severe irritation to the mucous membranes. The previously recommended dosing regimen of 3-3-3 (3 days of treatment, 3 days off, 3 days of treatment) has now been replaced by the 2-5-2 regimen, which is better tolerated (according to the manufacturer’s recommendation).

- Diclazuril (Vecoxan®, 2.5 mg/kg = 1 ml/kg): This is a better-tolerated, though less well-known medication. However, with regular use in larger populations, resistance can develop more quickly. Vecoxan is administered at a dose of 1 ml/kg in rabbits. For asymptomatic animals with mild infections, a single dose or treatment for two consecutive days may be sufficient. In cases of severe infestations or symptoms, the 2-5-2 regimen (2 days of treatment, 5 days off, 2 days of treatment) is recommended.

- Other Medications:

- Sulfamethoxypyridazine (Davosin®)

- Sulfathiazole (Eleudron®)

- Sulfaquinoxaline (Nococcin®)

- Sulfadimethoxine (Coccidiol SD®, Retardon®)

Vecoxan can often be administered gently with oats, banana, soaked Cuni Complete, or other favorite foods.

Effectiveness of Oregano and Garlic: Studies have confirmed the effectiveness of oregano and garlic against coccidia (see study: Nosal et al., 2014). They have been shown to be more effective than Baycox® and lead to better weight gain and lower coccidia shedding in comparison to untreated rabbits and those treated with Baycox®. Oregano oil is commonly used in such treatments, and a list of relevant products can be found below.

Prevention

In addition to veterinary treatment, there are several ways to support the healing process, and these measures can also be used for prevention.

The following products help support the gut flora and can indirectly combat coccidia (or prevent reinfection):

- RodiCare akut, Rodicolan, Colosan, and Herbi Colan

- Offer dandelion juice (available at health food stores, natural food shops, or online) for drinking.

- Oregano oil: Oregano oil is an excellent option for preventing coccidia and can help eliminate coccidia from affected populations. It is used in agriculture, often added to drinking water, and its effectiveness has been scientifically proven in studies (see Nosal et al., 2014) and supported by keeper experience. Additionally, the oil helps keep drinking systems algae-free, even in hot weather. Rabbits typically enjoy the mild oregano flavor. If rabbits are not drinking enough, oregano oil can also be added to their food. Combined with regular fecal testing, oregano oil can be a useful preventive measure against coccidia.

Warning! Never use pure essential oregano oil! The oils for food and water are extremely diluted (10%) and should only be added to water and food in very small amounts, drop by drop.

Feed Oils

- Probac Brockamp Oregano Oil: 5 ml per kg of food, 2-3 times a week, approx. €39.00/l

- ROPA-B FEEDING OIL 2%: 5 ml per kg of food, for 4-5 days a week, €15.95/l

- ROPA Poultry Feeding Oil: 5 ml per kg of food, for 4-5 days a week, approx. 500 ml/€14 = €28/l

- Röhnfried Darmwohl (Gut Health): 250 ml, €12.50 (€38/l)

Drinking Water Oils (with emulsifier) – Are the rabbits drinking enough?

(These can also be mixed into food or sprayed over food)

- Ropadiar Solution Oregano Oil 10%: 2–3 ml per 10 liters of water, approx. €39.90/l

- ROPA-B LIQUID 10%: 15 ml per 10 liters of drinking water, for 3-4 days a week, approx. €49.95/l

- DOSTO® Liquid 10%: approx. 20 ml per 1 liter of water, approx. €25/250 ml, or approx. €53.50/l

- Dosto WG Ropa Liquid 12%: 1 ml per 3 liters of drinking water, approx. €26/300 ml

- Becker Enterosan Liquid: 5 ml per 10 liters of water, €24.50/250 ml

- Röhnfried UsneGano Oregano-Lichen Mix, 3%: 3 ml per 1 liter of drinking water, approx. €46/l, daily or 2-3 times a week, 3 ml/liter

- Procura® 10% Solution: 5-20 ml per 10 liters of water

Administration Tips:

- Spray diluted oregano drinking oil onto fresh greens using a clean plant sprayer.

- Soak Cuni Complete in oregano oil-water mixture.

- Mix oregano oil into the rabbits‘ favorite food.

Nutrition for Coccidiosis

When managing coccidia infections, it’s important to provide a strengthening diet that promotes gut health, rich in herbs and fibrous greens. Beneficial herbs include oregano (or its cultivated form, marjoram), thyme, wormwood, dandelion, yarrow, parsley, tansy, sage, oak branches (both bark and leaves), black cumin, and blueberry plants. Other herbs that support the digestive system are also helpful.

For fresh greens, offer grass during the summer and leafy vegetables in the winter, such as bitter greens (e.g., dandelion, endive, arugula), Swiss chard, spinach, carrot tops, and celery. Also, include tannin-rich barks and twigs from plants like willow, hazel, oak, ash, fruit trees, fir, spruce, and pine.

Aim for a diverse range of plant-based foods to support a balanced diet. However, if the rabbit is underweight, avoid offering oats, as they can sometimes trigger yeast growth.

Hygiene & Disinfection

During the treatment of coccidiosis, strict hygiene is essential, especially in the litter boxes and feeding areas, to prevent the rabbits from re-infecting themselves.

- Hay and fresh greens should be provided in a hay rack to prevent contamination from poops. Water and food bowls should be cleaned thoroughly every day with hot water (>60°C) or in the dishwasher (using a hot cycle). Poops should be completely removed at least once a day to prevent the ingestion of sporulated oocysts, which take one to four days to develop. Litter boxes should be flushed with boiling water.

- The hutch, especially areas contaminated with poops, should be kept simple during treatment. Litter areas should be cleaned daily. Anything that has been soiled must be cleaned thoroughly, either mechanically or treated with hot water (>60°C), such as water from a kettle. The rest of the hutch should be cleaned thoroughly one or two times during the treatment phase, with floors being wiped down (for indoor enclosures) or treated with a steam cleaner, hot water (>60°C), or pressure washed with boiling water (for outdoor enclosures). However, steam cleaners can sometimes contribute to coccidia outbreaks due to the humid conditions, as they may not kill all the parasites, and the remaining ones thrive in such environments.

- Fabric items like blankets and rugs can be washed in the washing machine at high temperatures (min. 60°C). These should be removed from the hutch during the treatment. If the hutch has an earth floor, the top layer should be removed, and paving slabs should be laid down to prevent future coccidia outbreaks. As a temporary solution, the ground can be flooded with boiling water. A careful application of quicklime is also possible, but the rabbits must not be allowed into the treated areas during or immediately after this process.

- Outdoor enclosures on grass should be moved after the treatment, and the old area should not be used for grazing for some time. Quicklime and a weed burner can be used to treat the area. In general, overgrazing should be avoided (keep the stocking density low), and pasture rotation should be considered.

- Excessive hygiene measures (such as disinfecting everything, restricting access, boiling or cooking equipment) are unnecessary, stressful for both the animals and the owner, and can weaken the immune system.

- Common disinfectants are ineffective against coccidia. Suitable disinfectants include cresol-based products (e.g., Neopredisan), used at a 3-4% concentration and left to act for at least 2 hours. Capha DesClean is no longer effective against coccidia. However, these disinfectants are very toxic to rabbits, irritating to mucous membranes, and should only be used on surfaces that can be wiped clean (PVC, tiles, etc.). Surfaces that can absorb the disinfectant (e.g., wood, carpets, fabric) should not be used by rabbits afterward, as they become toxic. All wipeable surfaces should be thoroughly cleaned after disinfection. The rabbits must be removed from the area, and the space should be ventilated for a long time afterward.

- These disinfectants are also only suitable for limited use indoors and can be dangerous for people with allergies or asthma. Disinfection is generally not recommended unless done using a steam cleaner (>60°C), a flame device, or boiling water. It is important to expose surfaces to heat for an extended period and then ventilate the area promptly afterward. Boiling water is the simplest, most cost-effective, and most effective method of disinfection.

Sources

Abu-Akkada, S. S., Oda, S. S., Ashmawy, K. I. (2010): Garlic and hepatic coccidiosis: prophylaxis or treatment?

Bauer, C. (2006): Parasitosen des Kaninchens. In: Boch J., Supperer R.. Herausgeber: Schnieder, T. Veterinärmedizinische Parasitolige. 6. Auflage. Parey, Stuttgart. P. 561-575.

Baker D.G. (2007): Parasites of Laboratory Animals. Second Edition. American College of Laboratory. Animal Medicine, Blackwell Publishing, New Dehli.

Beck W., Pantchev N. (2006): Praktische Parasitologie bei Heimtieren. Kleinsäuger. Vögel. Reptilien.

Bienen. Schlütersche, Hannover.

Beck, W., Pantchev, N. (2009): Magen-Darm-Parasiten beim Kaninchen–Erregerbiologie, Pathogenese, Klinik, Diagnose und Bekämpfung. Kleintierpraxis 11.5 278-288.

Eckert J, Friedhoff KT, Zahner P, Deplazes P. (2008): Lehrbuch der Parasitologie für die Tiermedizin. 2. Aufl. Enke; Stuttgart

Ewringmann, A. (2009): Kotuntersuchung beim Kaninchen. Tierarzthelfer/in konkret, 5(02), 16-17.

Ewringmann, A. (2017): Leitsymptome beim Kaninchen: Diagnostischer Leitfaden und Therapie. Georg Thieme Verlag

Gugołek A., Kowalska D., Konstantynowicz M., Strychalski J., Bukowska B. (2011): Performance indicators, health status and coccidial infection rates in rabbits fed diets supplemented with white mustard meal.

Hein, J. (2016): Durchfall beim Kaninchen–Ursachen und Therapie. kleintier konkret, 19(S 01), 2-9.

Hein, J. (2017): Durchfallerkrankungen bei Kleinsäugern: Ursache, Diagnostik, Therapie. Schlütersche.

Kowalska D., Bielański P., Nosal P., Kowal J. (2012): Natural alternatives to coccidiostats in rabbit nutrition.

Kühn, T. (2003): Kokzidien des Kaninchens (Oryctolagus cuniculus)-Verlauf natürlicher Infektionen bei Boden-und Käfighaltung in einer Versuchstiereinheit.

Nosal, P., Kowalska, D., Bielanski, P., Kowal, J., & Kornas, S. (2014): Herbal formulations as feed additives in the course of rabbit subclinical coccidiosis. Annals of parasitology, 60(1).

Schmäschke R. (2013): Die koproskopische Diagnostik von Endoparasiten in der Veterinärmedizin. Schlütersche; Hannover

Schmäschke, R. (2014): Parasitologische Kotuntersuchung des Kaninchens. kleintier konkret, 17(S 01), 31-33.

Starkloff, A. 2010: Einfluss von Wetterfaktoren und sozialer Umwelt auf den Endoparasitenbefall juveniler Wildkaninchen (Oryctolagus cuniculus L.) Diss. University of Bayreuth

Zinke, J. (2004): Ganzheitliche Behandlung von Kaninchen und Meerschweinchen: Anatomie, Pathologie, Praxiserfahrungen; 14 Tabellen. Georg Thieme Verlag

4

4

4