Many rabbit owners eventually reach a point where they want to expand their group in order to keep more animals.

Often, this simply involves introducing a few new rabbits and providing a larger enclosure. However, keeping a large group of rabbits comes with its own unique challenges and is only recommended for experienced owners, as it requires special considerations.

From our experience, the initial excitement often turns into feelings of being overwhelmed.

That’s really unfortunate, because few things are as rewarding as watching a happy, well-functioning group of rabbits. Since there’s still very little specific information available for those keeping large groups, we’d like to share some tips and tricks in this article to help make it work.

Contents

- Bonding – Not Every Rabbit Is Suitable

- The Enclosure – Creating Harmony Through Structure

- The enclosure, its size, and its layout can determine whether a large group remains harmonious in the long run.

- Bullying and Hierarchy Fights

- Many factors can increase the likelihood of fights among rabbits, such as:

- When Are Fights Still Normal?

- What to Do if They Are Bullying Each Other Severely?

Bonding – Not Every Rabbit Is Suitable

The bonding process is essentially the same as with smaller groups. However, since a neutral space is often not available when dealing with larger groups, bonding can also take place, for example, in a garden run with separated nighttime enclosures. That said, this method should only be used by very experienced rabbit owners!

It’s important to understand that bonding pairs is usually much easier and less intense than bonding larger groups. Pairs often form a kind of “partnership of convenience,” since they don’t have a choice between different companions. Once the group grows to four or more rabbits, they begin to choose their preferred partners. Larger groups are more dynamic — there may be some chasing, and special friendships will form.

There are also rabbits that simply cannot cope with being part of a large group or just don’t fit in well. These individuals should instead be kept in a pair with a rabbit of the opposite sex.

The Enclosure – Creating Harmony Through Structure

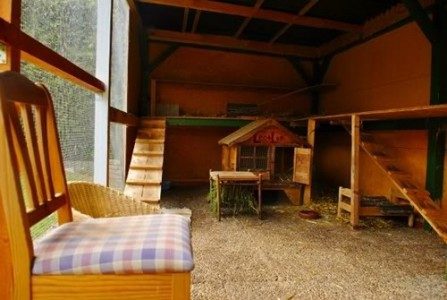

The enclosure plays a crucial role in maintaining harmony within a large rabbit group. A simple setup is not enough — size, specific furnishings, and thoughtful layout are key to ensuring that even lower-ranking rabbits feel comfortable and safe.

The following basic guidelines should be implemented whenever possible:

- Multiple levels are a must: Each level should have both an accessible entrance and exit to avoid dead ends and prevent rabbits from feeling trapped.

- The enclosure should be divided into different zones, for example by adding inner walls or combining a large aviary with a garden shed.

- Houses and hiding places (such as open-fronted shelters or dog houses) should have at least two entrances to allow escape routes and reduce tension.

- An appropriate minimum size is essential to give all rabbits enough space to avoid conflict and retreat if needed.

- Several hay racks and fresh food stations to prevent competition and ensure all rabbits can eat in peace.

- Multiple litter trays, well distributed throughout the space, to keep the area clean and reduce territorial disputes.

The enclosure, its size, and its layout can determine whether a large group remains harmonious in the long run.

Especially for large groups, it’s important to include generously sized multi-level areas, as well as plenty of hideaways and spatial divisions. This is the only way to ensure that lower-ranking rabbits also have a fair chance to find their place and feel comfortable over time.

Bullying and Hierarchy Fights

This topic is one of the main reasons why some rabbit owners, out of frustration, give up on group housing — or worse, start keeping rabbits alone. But that should never be the solution!

There are many reasons why hierarchy disputes arise in rabbit groups, but the most common ones include:

- „Spring fever“: In spring, many groups experience a re-establishment of the hierarchy. Hormones signal that it’s time to reproduce, and every rabbit wants the highest possible rank — the higher the rank, the more likely their offspring would survive in the wild.

- Disregarding hierarchy rules: For example, when a lower-ranking rabbit steals food from a dominant one or behaves too boldly, it may be corrected or “educated” by the others.

- A rabbit becomes weaker due to illness or aging, and lower-ranking rabbits may then try to challenge and take its place, often leading to more intense conflicts.

- A group member dies or is removed: This can destabilize the existing hierarchy, prompting the rest of the group to fight over rank again.

- Pain-related aggression: Rabbits in pain often become irritable or aggressive. These health issues are often hidden, such as uterine problems in females.

- A previously sick rabbit recovers: Once healthy again, it may try to climb the social ladder, leading to renewed disputes.

- Poor or incomplete bonding: If rabbits weren’t properly introduced and never had the chance to fully establish a hierarchy, fights may break out later — often once they’re back in their territory.

- Neutering/spaying: Any changes here — even spaying females — can disrupt the hierarchy, requiring a new round of ranking disputes.

- Temporary separation: If rabbits have been apart for a while and are reintroduced, they often have to re-establish their ranks.

- Intact males: Keeping unneutered bucks together almost never works. Even after years of peace, they may suddenly fight to the death. Two does without male companionship often stop getting along during puberty (around 8–12 months), or even earlier or later. Mixed-sex groups (with neutered males) are always preferable.

- Group size matters: Groups of four to eight rabbits tend to be more unstable and prone to frequent rank disputes. Very small groups or larger ones (eight, nine, or ten rabbits and more) are often much more peaceful.

- Young rabbits (ages 1 to about 4.5 years) tend to have more conflicts than older, senior rabbits.

…

Many factors can increase the likelihood of fights among rabbits, such as:

- Lack of food

- Lack of space (enclosures that are too small)

- Springtime (hormonal changes)

- Unbalanced sex ratios (e.g., five neutered males and one female), or all-male/all-female groups

- Groups that haven’t lived together for long (groups that have been together longer tend to be more stable)

- Dead ends in the enclosure, which can trap lower-ranking rabbits

- Extremely large spaces (over 500 m²), which can make group dynamics harder to maintain

- Too few hiding spots or no visual barriers, making it impossible for rabbits to escape each other’s view

- Hormonal imbalances in individual rabbits, such as those going through puberty (around 8 months old), especially in same-sex pairings

- Sick rabbits or those that have been temporarily removed from the group (e.g., after neutering)

Putting together a well-functioning group isn’t easy.

The rabbits’ personalities should be compatible, and the gender ratio needs to be carefully considered. In most cases, a group with more females or a balanced male-to-female ratio works best. If the females or males are already having serious issues among themselves, it’s usually better to introduce rabbits of the opposite sex.

If a rabbit consistently shows problematic social behavior within a group, it may be better off living in a bonded pair instead.

Sick, old, or weakened rabbits are sometimes (but not always) bullied and may not be suitable for living in large groups. As a result, many owners have chosen to keep these rabbits in a separate group. Within such a group, these rabbits are usually much more harmonious and content.

Rabbits with different dietary needs (e.g., dental issues, increased energy requirements, obesity, etc.) can be challenging to manage in a large group. Ideally, it’s best to feed a low-energy diet with plenty of fresh greens, and separate rabbits with special needs for one or two feedings a day. Alternatively, a chip-controlled feeding bowl can be used to provide supplemental food tailored to their individual needs.

Unfortunately, a large group is often very lively, and it takes a lot of experience from the owner to properly assess the behavior and respond accordingly.

When Are Fights Still Normal?

No matter how intense the fights look, how much fur is flying, or how much the rabbits are fighting, as long as none of the following criteria are met, the fights are generally normal:

- There are severe injuries (not just scratches or „accidental“ wounds, but bites that require treatment).

- The rabbits fight for weeks without any periods of peace or reconciliation between the fights.

- A rabbit presses its head against the wall and refuses to move, while the others continue to bite its back.

- A rabbit has an intense fear of the other rabbits and remains in constant flight, showing no improvement after several days.

- The rabbits bite each other so hard that they are lying on the ground (not just quick bites).

What to Do if They Are Bullying Each Other Severely?

- Are all the rabbits healthy? Has a rabbit possibly moved up or down the social hierarchy? For example, did a rabbit become dominant after recovering from an illness, or is it struggling with a drop in rank, such as after being neutered and not adjusting well?

- Rabbits often notice health issues before we do. Symptoms may appear days later, which could explain the aggression.

- Is the group composition suitable? Is every rabbit fit for life in a large group? Perhaps one rabbit would be better off living in a pair.

- Is the enclosure well-structured and suitable for the number of rabbits (size and layout)? Can the lower-ranking rabbits easily escape from the dominant ones? Have dead ends been avoided?

- Are two rabbits just incompatible? Or are there two rabbits that both want to be the „alpha“ and refuse to give up that position?

- Are all the males neutered?