„My rabbit is not eating.“ „My rabbit has a stomachache.“

„Food refusal in rabbits is always an absolute emergency! It can be fatal within hours! Do not waste time and do not wait!“

Food refusal and digestive disorders in rabbits are very serious issues and often lead to death. That’s why rabbit owners should be familiar with them and know how to act in an emergency.

In most cases, affected rabbits do not actually have a primary digestive problem, but rather another illness that leads to food refusal, which can then result in gastric dilation.

Contents

- First Aid

- How to Recognize Gastric Dilation?

- Causes – What Causes Gastric Dilation?

- Development – How Gastric Dilation Occurs

- Diagnosis – Is it Gastric Dilation?

- Understanding Diagnoses

- Treatment – How can you help?

- Diet & Care for Sick Rabbits

- Cause – This needs to be investigated!

- Nutrition for Prevention

- These types of feed are specifically effective against bloating and help regulate digestion.

- Diet During Shedding (Preventing Hairballs)

- The following dietary and housing mistakes contribute to the formation of life-threatening hairballs:

- Malt Paste? Bezo-Pet Paste?

- Before-and-after photos

First Aid

Of course, emergency medication can be given initially. Every rabbit owner should have Simethicone (e.g., Sab Simplex 0.5–1 ml/kg, 3–6 times daily) or another product containing Simethicone or Dimethicone (which works more slowly), as well as Colosan/RodiCare akut (7–10 drops, 3 times daily) or a similar emergency medication at home.

Additionally, the rabbit’s abdomen should be gently massaged, and if its ears feel cold, its body temperature should be measured with a thermometer (see First Aid).

However, if there is no rapid improvement, a rabbit-savvy veterinarian should be contacted immediately. Depending on the rabbit’s condition, waiting up to one hour may be acceptable.

If the rabbit is dehydrated (skin fold does not return immediately) or has hypothermia (temperature below 38.5°C / 101.3°F), a vet should be consulted immediately after administering the medication!

During transport to the vet, the rabbit must be kept warm. Place it on a blanket with a warm (not too hot!) water bottle or a Snuggle Safe underneath, and cover it with another blanket.

How to Recognize Gastric Dilation?

Affected rabbits are usually quieter than normal, withdraw, and no longer engage in everyday activities. They also refuse to eat, even turning down their favorite treats. A lack of poop may often go unnoticed in group housing. Experienced owners may be able to feel an enlarged, distended abdomen. Some rabbits appear round and bloated, while others may react painfully when their abdomen is touched.

The condition progresses very rapidly, and some rabbits may already be in shock, accompanied by hypothermia (below 38.5°C / 101.3°F) and dehydration (a raised skin fold does not immediately return to normal, but slowly sinks back).

The diagnosis can only be made by a veterinarian, who will need to perform an X-ray, as other illnesses can present with similar symptoms.

Causes – What Causes Gastric Dilation?

- Any form of food refusal, whether caused by pain (such as organ diseases, dental issues, ear infections, etc. – which are often not visible from the outside), leads to dehydration of the intestinal contents. Due to weak muscle movement, the contents are not transported properly, meaning fermentation issues occur, and a dry, sticky food mixture forms (sometimes with small hairballs that were already present).

- Pure hairballs are rarer than commonly assumed! Especially during molting, the ingestion of a lot of fur (from grooming their own coat, grooming other rabbits during molting, or from compulsively pulling out their own fur) can form a solid mass in the intestines, leading to blockages (bezoar, hairballs). However, hairballs typically only cause problems if the rabbit is not fed a purely fresh food diet, but is instead given some type of dry food, oats, etc., or if fresh greens are not available 24 hours a day.

- Constipation is strongly encouraged or even triggered when the rabbit is fed very dry, energy-dense, or protein-rich food. The dry food mass cannot be moistened and does not move through the digestive system. Natural food consists of 70-80% moisture (fresh food), which is why a rabbit’s digestion is designed for a very moist food transport.

- A parasitic infestation with coccidia, less commonly with yeast fungi or worms, can cause constipation. Tapeworm cysts can even lead to an obstruction. Submit a poop sample from three days to rule out parasites.

- Intestinal inflammations (enteritis, enterocolitis), especially bacterial, lead to recurring sudden food refusal.

- Many rabbits occasionally stop eating because they feel nauseous. This is often due to stomach disorders, particularly in rabbits with chronic illnesses, stressed animals, or those receiving repeated pain medication. A migrating hairball or intestinal inflammations can also be the cause. Such animals may need to be given acid blockers (like Omeprazole) or stomach protectants (like Sucralfate, Ranitidine) on a long-term basis.

- Malignant or benign tumors (neoplasms) (very rare).

- Swallowed currant seeds, pellets, or dried vegetables/fruit, or unsoaked flaxseeds can swell in the intestines (rare).

- Tissue adhesions after female neutering (rare).

- Eating (clumping) cat litter, straw pellets, food pellets, coconut bedding, cardboard, fabrics, carpets, Vetbeds/Isobeds, or other things that swell or clump strongly in the stomach and intestines (e.g., foreign objects).

- Mold in the food or living area.

- Foreign objects, such as decorations, plastic, etc., that have been ingested – the possibilities are endless.

- Lack of access to drinking water can cause constipation.

- Increased ambient temperature or heat (which can disrupt the gut flora).

- Infectious diseases.

- Strangulated hernias or prolapsed intestines that block the digestive system.

- Abdominal abscesses.

- Space-occupying diseases of the uterus or other organs.

- Lack of movement, a living environment that restricts movement, and/or obesity can exacerbate constipation.

- A diet low in fiber, dry, or poorly digestible food generally worsens constipation in rabbits.

- Suddenly introducing large amounts of dry food or treats often leads to constipation.

- Hypothyroidism can also trigger constipation.

- Long periods without eating or rapid eating (gulping) can often lead to bloating. Offer your rabbits plenty of fresh greens multiple times a day so they can eat at their own pace and consume food consistently throughout the day and night.

- Obesity can also push on the intestines, making constipation more likely.

Important: The outdated information that feeding cabbage causes bloating is still commonly spread. This is not true! Rabbits that are fed a healthy diet can tolerate large amounts of cabbage without any issues. If cabbage is not tolerated, it is usually due to the feeding of pellets or other unhealthy food that burdens the digestive system, potentially causing intolerances to cabbage, grass, and other fresh foods.

Development – How Gastric Dilation Occurs

When food is refused, the stomach and intestinal contents are not moved forward, as rabbits have little muscle strength or an obstruction is present. This causes the intestinal contents to dry out.

This leads to fermentation processes, where pathogenic bacteria proliferate, resulting in gas production. Saliva flows back into the stomach, and in combination with the fermentation processes, the stomach contents become liquefied, forming a gas bubble.

In obese animals, the stomach is less able to expand because the fat tissue constricts it. As the stomach enlarges, it presses on the heart and lungs, leading to circulatory failure and death!

⚠️ Dysbiosis (disruption of the gut flora) occurs very quickly, leading to difficulty breathing and circulatory collapse, which can result in death!

Diagnosis – Is it Gastric Dilation?

Make sure to see a veterinarian who is not only specialized in small animals (dogs & cats), but also in exotic pets (rabbits and rodents)! Only veterinarians with specific additional training can treat rabbits, as they are only a minor subject in veterinary studies.

The temperature of rabbits should not drop below 38.5°C. Stress can cause an increase in temperature, which should not be confused with fever. If the temperature is lower, it indicates hypothermia. This affects the heart, circulation, and stomach acid production. An increase in temperature, even up to fever, can accompany other conditions and may lead to food refusal, which can result in gastric dilation.

Additionally, a bowel obstruction can occur due to paralysis of the intestinal muscles (paralytic ileus). Central nervous problems such as incoordination, movement disorders, altered consciousness (reduced blood flow to the central nervous system), and even coma, may also develop. Further progression can lead to liver and kidney failure, as well as difficulty breathing.

Life-saving immediate measures must be taken starting from moderate hypothermia before diagnostic procedures can be carried out. The further the condition progresses, the more severe the organ damage becomes, which may later be irreparable.

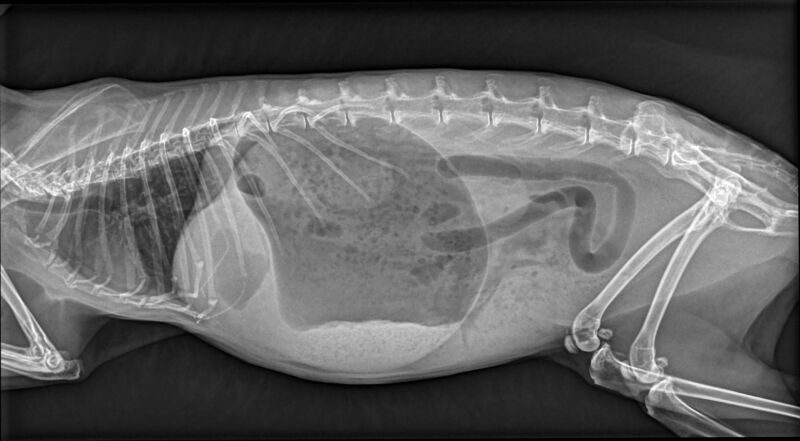

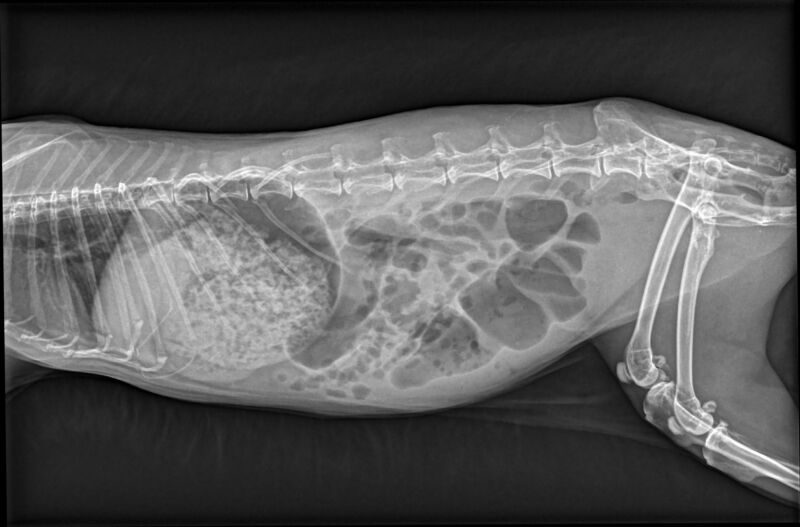

The veterinarian will palpate the animal, measure the temperature, and definitely take X-rays from two views, with the lateral view being the most informative. The enlarged, fluid-filled stomach with gas portions can be seen on the X-ray. If the gas bubble is positioned centrally („mirror image“) or laterally, the prognosis is worse. A rabbit-experienced veterinarian will consider X-rays in such a situation as essential. [Interpretation assistance for veterinarians]

The location of the obstruction can be identified by gas accumulation or contrast studies. The section before the obstruction (ileus) will be overfilled, and the section after it will be gassy. Is the obstruction at the stomach outlet or in the small intestine? Contrast X-rays can also be useful in some cases (only iodine-based contrast media, not barium sulfate!). The contrast medium will not settle in hairball-food clumps, so they can become visible depending on their location. Contrast media can overload digestion, damage the intestinal walls (leading to rupture), and disrupt the cecal bacteria balance, potentially causing life-threatening bloating or even obstructions. They should not be used if the rabbit is dehydrated. Therefore, their use is carefully considered.

Important: Insist on X-rays at your veterinarian! This is the only way to reliably diagnose gas buildup and locate blockages—palpation alone is not sufficient!

The temperature provides important clues about which further diagnostic tests are necessary. In cases of hypothermia, an obstruction should always be ruled out, while fever may indicate conditions such as appendicitis (inflammation of the appendix at the cecum).

A blood test can offer a fairly reliable prognosis. Around 70% of rabbits with an intestinal obstruction show significantly elevated blood glucose levels. In one study, the average glucose level in affected rabbits was 24.7 mmol/L, with those exceeding 20 mmol/L (= 360 mg/dL) having a poorer prognosis. Liver values are often elevated in affected rabbits, and in such cases, an ultrasound should be performed to rule out a liver lobe torsion. A blood test is recommended to assess prognosis and detect potential complications such as liver and kidney damage, inflammation, or glucose imbalances.

A urine test (urine test strips) can help evaluate metabolic status and thus prognosis. An acidic urine pH may indicate a catabolic metabolic state, which is associated with a poorer prognosis.

Since liver lobe torsion can sometimes occur without elevated liver values in blood tests, an ultrasound of the liver is recommended. This may also allow for an assessment of the digestive system.

Another cause of food refusal is appendicitis (inflammation of the appendix at the cecum). Affected rabbits often have a fever and respond with pain when palpated. Typically, a tubular mass can be felt in the abdomen. In about half of these cases, rabbits have a low glucose level (other causes include intestinal inflammation, dental diseases, and pancreatic disorders). A low calcium level and regenerative anemia can also be detected in some rabbits. In cases of fever or other signs, an ultrasound of the cecum should be performed. Appendicitis is often not diagnosed because it is a rabbit-specific condition and rarely occurs in dogs and cats.

In cases of elevated environmental temperatures or digestive disturbances in multiple rabbits, a bacterial stool sample should be taken to rule out bacterial intestinal inflammations.

Gastric dilation before and after 2 hours of treatment.

Understanding Diagnoses

Gastric Dilation – An enlarged stomach filled with liquid, food slurry, and gas (detectable via X-ray), often caused by ileus, overly dry or poorly structured food, or food refusal (as a result of pain or other diseases).

Ileus – Disruption of food passage due to a blockage at the stomach exit or in the small intestine (e.g., caused by hairballs, bezoars, carob pods, foreign objects, carpet fibers, inadequately chewed food (dental diseases), or intestinal paralysis).

Tympany (Bloating) – Gas buildup in the digestive tract, often resulting from a blockage or lack of food movement (e.g., food refusal due to pain, intestinal paralysis, etc.). The causes are diverse.

Gastric Overload – A stomach overloaded with food slurry, usually rare, caused by rapid consumption of large amounts of food (due to strict feeding schedules or sudden dietary changes) or the intake of swelling foods (e.g., pellets, chopped hay, flour-based products).

Constipation – A blocked digestive tract but without a complete blockage (e.g., from ingested bedding, improper diet, etc.).

Stasis (Lagging, Congestion) – Stagnation of intestinal contents.

Coprostasis – Stagnation of feces in the colon, often caused by dietary mistakes, insufficient movement, or dehydration.

Treatment – How can you help?

In general, the animal should first be stabilized by the veterinarian. This may involve administering warmed infusions (which should be given intravenously depending on the circulatory state), heat, possibly oxygen, painkillers (e.g., buprenorphine or novalgin, 10-20 mg/kg, 2-3 times a day, possibly combined, but no meloxicam (e.g., Metacam)!).

In cases of gastric overload, medication typically doesn’t reach the small intestine in time to be absorbed by the body. This means that as much as possible should be administered via an intravenous access to ensure it is effective and to avoid further burdening the stomach.

T

- Anti-nausea treatment: Medications like Metoclopramide (Emeprid/MCP) can be used at the beginning at a dosage of 5mg/kg, preferably administered via injection. Afterwards, the dosage can be reduced to 0.2-1mg/kg, 1-3 times daily. Metoclopramide should not be used longer than three days and, if necessary, should be gradually tapered off. Additionally, Metoclopramide should not be used in cases of constipation (contraindication). Maropitant is often highly effective in alleviating nausea.

- Gastrointestinal motility: While the efficacy of Metoclopramide for promoting gastrointestinal movement in rabbits is not scientifically proven, it seems to work well, particularly in higher doses. The effectiveness of Cisapride is uncertain based on current studies. However, Lidocaine infusions (100μg/kg/min intravenously over two days) are proven to have a pain-relieving, anti-endotoxic, anti-inflammatory, and prokinetic effect. Mirtazapine (3mg/kg once daily) can also be effective, but this requires hospitalization and monitoring.

- Acid blockers and stomach protection: Omeprazole as an acid blocker and Sucralfate or Ranitidine as stomach protectants may be used. These can also help prevent acidosis (excessive acidity in the body).

- Metabolism support: Butafosfan and Cyanocobalamin (Vitamin B12) Catosal may be used to stabilize the metabolism.

- Gas reduction: Simethicone/Dimethicone is used to reduce gas bubbles, making it easier for them to be expelled.

- Constipation relief: Lactulose (e.g. Albrecht brand) softens the stool by drawing water into the intestine, helping with constipation relief.

- Phytotherapeutics (e.g., Colosan, RodiCare akut, or similar preparations) can be helpful as they stimulate blood circulation in the intestinal mucosa, have antispasmodic effects, and prevent further gas production through their antimicrobial properties.

- Plant oils can have a laxative effect in the stomach and first section of the small intestine, and when administered in larger quantities, a sufficient amount of oil can reach the intestines. Additionally, they stimulate the intestinal muscles via motilin. However, be aware that plant oils are absorbed in the small intestine by around 80% and may be partially saponified, potentially not reaching the areas where they are needed. Paraffin oil, on the other hand, is not absorbed but has been suspected of disrupting the intestinal flora, though this has not been proven and is not known in horses, for example. Paraffin oil should never be administered in cases with dry cecal contents!

- Spasmolytic drugs (e.g., Buscopan) should never be used for digestive disorders in rabbits!

- Massage techniques can be used to help relieve constipation or move lumps, allowing the food mixture to move forward. The veterinarian can indicate the exact location for targeted massage after reviewing the X-ray. Stretching movements are generally effective in relieving the issue.

- Encouraging movement can also help: try to carefully stimulate the rabbit to move, but also allow it time for rest.

- If there is suspicion of an overgrowth of harmful bacteria (which can be detected through a differential blood test showing a pseudoleft shift, a sign of inflammation, often relevant in cases of severe bloating), an antibiotic like Enrofloxacin may be administered. Metronidazole can also be helpful. Do not use PLACE antibiotics such as Penicillin, Lincomycin, Ampicillin, Amoxicillin, Clindamycin, Cephalosporins, or Erythromycin in rabbits.

- In cases of true hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), urgent glucose administration is required. However, according to a 2012 study by Harcourt-Brown, this occurred in only 1.7% of cases.

Important! In the case of a blockage or when the stomach is massively overloaded, forced feeding and/or large amounts of medication (e.g., Lactulose) can lead to a rupture of the very thin stomach wall (gastric rupture)! Additionally, the stomach is further overloaded by the feeding paste, which presses against the diaphragm, restricting the respiratory function of the very small rib cage. This can potentially lead to circulatory problems, even resulting in death! If a blockage is ruled out and the digestive symptoms persist, but the stomach is not overloaded, thin liquids can be used for feeding.

Instead, stomach contents can be drained through a tube to stabilize circulation in an acute case. However, this must be carefully considered, as the tube can also cause a tear in the stomach wall.

✂️ Surgery? If, despite all efforts, the medication treatment does not help, the veterinarian, in consultation with the owner, will opt for a surgical procedure. However, conservative treatment should be preferred, as surgery carries significant risks, and the prognosis with conservative treatment and timely, intensive care is usually quite good. If the blockage is located further back in larger sections of the intestines, it may be possible to massage the food-hair-stool mixture out after opening the abdominal cavity, without cutting into the intestines. Almost always, after opening the abdominal cavity, the hairball can be manually pushed or massaged into the large intestine. Alternatively, the hairball can be massaged back into the stomach and then crushed through kneading. In some cases, gas can also be released using a syringe. If the stomach or intestines need to be cut open, the prognosis is worse, but it is still advisable as a last resort. If a foreign body is firmly lodged, it may quickly lead to the death of the intestinal wall at that point.

Diet & Care for Sick Rabbits

During illness, it is best to offer the rabbit a variety of fresh aromatic and wild herbs, as well as alfalfa, clover, cabbage, and meadow herbs. However, the main priority is that the rabbit eats; what it eats is secondary.

Cause – This needs to be investigated!

Food refusal in rabbits has many possible causes. The cause should be identified, as it can prevent further issues. Additionally, often there are underlying illnesses causing significant suffering that need to be treated promptly.

It could involve any condition that causes pain, such as uterine diseases, ear infections, or diaphragmatic hernias.

Nausea from kidney failure, kidney stones, or gastritis is also a common reason.

Often, well-meaning but incorrect feeding is the underlying cause. Too many carbohydrates (fruit, seeds, tuber vegetables, dry food), poorly structured and energy-dense foods (such as dry food or pellets), and dental diseases (often caused by poor food choices) are major contributors.

Stress can also lead to gastric dilation. Stress activates the sympathetic nervous system, which inhibits stomach function.

Nutrition for Prevention

There are always rabbits that tend to have digestive issues due to previous improper feeding. Of course, the first step should be to change the diet. A diet with unlimited green forage (preferably from the wild) is the best choice for digestive problems, as it ensures a steady and regulated workload for the digestive tract. Any form of grains and commercial feed (dry food, pellets, mixed feed…) should be gradually discontinued. Grains and seeds as energy food can be reintroduced in limited quantities once digestion is stable again (no more than 1 teaspoon per day per animal, let seeds like flaxseeds or chia seeds swell before feeding them!). Commercial feeds of any kind are not recommended due to their digestive-damaging effects and questionable ingredients.

After the illness, a green-rich diet (as much meadow herbs and/or vegetable greens as they want), supplemented with vegetables and hay, is recommended. Fresh food intake is especially important to prevent constipation, as a dry diet inevitably leads to recurring constipation.

Also, highly diluted plant juices (pure fruit juice or carrot juice without added sugar) can be offered to increase fluid intake. Pure herbal teas are also suitable.

Soaked flaxseeds or psyllium husks (1 teaspoon (5g) soaked in 100ml water overnight, and then 1-3 teaspoons per animal mixed with grated carrot, the remainder can be frozen in ice cube trays and thawed in portions) or possibly Lactulose from Albrecht (softens stool by drawing water from the intestines) can support the relief of constipation. RodiCare Hairball has also proven effective.

These types of feed are specifically effective against bloating and help regulate digestion.

- Kitchen Herbs: Dill, peppermint, lemon balm, basil, parsley, thyme, oregano, sage, chives, wormwood, lovage, lavender, nettle

- Forest and Meadow Herbs: Bear’s foot, dandelion, oak bark and leaves, wild garlic, true chamomile, pussy willow and branches, yarrow, chicory

- Seeds: Dill seeds, fennel seeds, caraway, aniseed

- Vegetables: Fennel, ginger

Diet During Shedding (Preventing Hairballs)

To prevent potentially life-threatening hairballs (hair clumps in the digestive tract), it’s important to actively remove loose fur, especially during shedding season. You can do this by regularly brushing the loose fur out or gently stroking the fur with your hands or dampened rubber gloves. A plucking brush works ideally for removing loose fur. You can also place brushes in confined spaces, tunnels, or narrow areas of the habitat so that less tame rabbits can brush themselves while passing through. However, I advise against excessive brushing, as experience shows this may lead to more fur being ingested. If there’s a lot of loose fur, it can be removed once, but daily brushing, for example, might worsen the problem.

A supporting diet can help prevent hairball formation. The ideal diet would include a large amount of meadow plants, herbs, and leaf vegetables available in unlimited amounts. Fresh greens should be offered freely, day and night. This is the best form of hairball prevention! Dry foods (including dried herbs, excessive hay, etc.) can contribute to hairball formation. RodiCare Hairball and Lactulose have proven effective. Psyllium husks, soaked and mixed with delicious vegetables (grated) or fruit (shredded), can also be offered. This is a cost-effective alternative to RodiCare Hairball.

And here’s something really important: Ensure your rabbits have plenty of space to move around, both day and night, as this helps solve hairball problems. In indoor and protected outdoor environments, extra vacuuming should be done during shedding seasons, as the wind, which helps remove fur, is absent. In extreme cases, it might help to trim indoor rabbits‘ fur so that the ingested hairs are significantly shorter.

When dealing with hairballs, be sure to brush the affected rabbit and all other rabbits in the group carefully every day, so that no more fur is ingested, which could worsen the problem. In indoor settings, regular vacuuming has proven to be helpful.

By the way, poops chains are not a concern—in fact, the opposite is true. When poops chains appear, it means the fur is being excreted and not remaining in the intestines to form hairballs.

Lastly, be sure to offer your rabbits plenty of space to move, day and night, as this will help resolve hairball issues.

The following dietary and housing mistakes contribute to the formation of life-threatening hairballs:

- Hay as the main diet with fresh food portions.

- Hay as the main diet with dry food and fresh food (the dry food also absorbs all the water).

- Hay-based diet, dry food-based diet, and feeding methods with low fiber content: Too much concentrated food (seeds, grains, etc.), commercial dry food, etc. Dry food not only absorbs moisture but also has very little water content and minimal fiber.

Malt Paste? Bezo-Pet Paste?

The composition of these pastes is mostly incorrect or not listed on the packaging. Usually, only the effect is described, which according to the packaging is based on three factors: plant oils and fats, fiber, and malt, which is supposed to aid digestion. Cat pastes are almost identical to rabbit pastes and are often used by many pet owners. However, these pastes are only high in fiber for cats. Any rabbit food (herbs, hay, twigs) contains significantly more fiber than these pastes! Rabbits consume far more fiber with a normal diet than cats do. What is considered high in fiber for cats can be classified as low in fiber for rabbits. Malt is made from grain sprouts that are dried and processed after a short germination period. Often, it is poorly digestible wheat. Additionally, there is a lot of additives that can harm rabbits. Even the effect of the plant oils is not present, as they are already absorbed in the small intestine. These pastes contain no active ingredients that could help with hairballs. Instead, they contain many harmful substances, and most of the ingredients are not listed.

A better alternative is RodiCare Hairball, which is based on swollen psyllium seeds.

Before-and-after photos

Yuki with stomach pain

Elli with hairballs

Elli had a large clump of hair, and possibly some textiles (carpet, etc.), in her stomach. Unfortunately, it couldn’t be resolved with medication. Therefore, surgery was recommended: Through an abdominal incision, her stomach was opened and emptied. It took nearly two weeks before she was eating on her own again. To feed her, I had to put her in a pillowcase (a tip from the vet), as it was impossible to reach her mouth otherwise (she had her jaw tightly clenched). But all the sleepless nights were worth it! She’s doing great now.

Sources/For further reading, among others:

Böhmer, E. (2005): Röntgenologische Untersuchung bei Hasenartigen und Nagern (Schwerpunkt: Magen-Darm-Trakt, Harntrakt, Wirbelsäule). Tierärztliche Praxis Ausgabe K: Kleintiere/Heimtiere, 33(02), 115-125.

Böttcher, A. (2017): Untersuchungen zur Magendilatation bei Heimtierkaninchen (Oryctolagus cuniculus) (Doctoral dissertation, Freie Universität Berlin).

Cheeke, P. R., Cunha, T. J. (2012): Rabbit feeding and nutrition. Elsevier.

Davies, R. R., & Davies, J. A. R. (2003): Rabbit gastrointestinal physiology. Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice, 6(1), 139-153.

Di Girolamo, N., Petrini, D., Szabo, Z., Volait-Rosset, L., Oglesbee, B. L., Nardini, G., … & Binanti, D. (2022): Clinical, surgical, and pathological findings in client-owned rabbits with histologically confirmed appendicitis: 19 cases (2015–2019). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 260(1), 82-93.

Drescher B. (2014): Magenüberladung beim Kaninchen. Kleintier konkret 2: 12–16

Eckert, Y. (2020): Stillstand: Der Ileus beim Kaninchen. kleintier konkret, 23(S 01), 2-10.

Feldman, E. R., Singh, B., Mishkin, N. G., Lachenauer, E. R., Martin-Flores, M., & Daugherity, E. K. (2021): Effects of Cisapride, Buprenorphine, and Their Combination on Gastrointestinal Transit in New Zealand White Rabbits. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science.

Harcourt-Brown, F. M. (2007): Gastric dilation and intestinal obstruction in 76 rabbits, Veterinary Record 161, 409-414

Harcourt-Brown (2007): Gastric dilation and intestinal obstruction in 76 rabbits. Vet Rec 161 (12): 409–414

Harcourt-Brown TR. (2007): Management of acute gastric dilation in rabbits. J Exotic Pet Med. 16 (3): 168–174

Hein, J. (2009): Anorexie beim Kaninchen–diagnostische Aufarbeitung und erster therapeutischer Ansatz. Tierärztliche Praxis Ausgabe K: Kleintiere/Heimtiere, 37(02), 129-138.

Hein, J. (2016): Notfälle beim Kleinsäuger – erkennen und reagieren.

Hein, J. (2018). Röntgenbildinterpretation Magen-Darm-Trakt Kaninchen. kleintier konkret, 21(S 01), 12-20.

Huckins, G. L., Tournade, C., Patson, C., & Sladky, K. K. (2024): Lidocaine constant rate infusion improves the probability of survival in rabbits with gastrointestinal obstructions: 64 cases (2012–2021). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 262(1), 61-67.

Kreis ME, Jauch KW. (2006): Ileus aus chirurgischer Sicht. Differenzialdiagnose und therapeutische Konsequenzen. Chirurg. 77 (10): 883–888

Köstlinger, S. (2014): Notfälle beim Kaninchen. kleintier konkret, 17(S 02), 2-7.

Lichtenberger M, Lennox A. (2010): Updates and advanced therapies for gastrointestinal stasis in rabbits. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 13 (3): 525–541

Manning P.J. Ringler D.H. Newcomer C.E. (1994): The biology of the laboratory rabbit. Academic Press, San Diego: 63-71

Nickel, R., Schummer, A., & Seiferle, E. (2004): Lehrbuch der Anatomie der Haustiere—Band II Eingeweide. Parey, Stuttgart.

Müller, K. (2014): Magendilatation beim Kaninchen–Was ist zu tun? kleintier konkret, 17(02), 16-20.

Ozawa, S., Thomson, A., & Petritz, O. (2022): Safety and efficacy of oral mirtazapine in New Zealand White rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine, 40, 16-20.

Schnabl, E., Böhmer, E., & Matis, U. (2009): Diagnostik und Therapie des Magenbezoars beim Kaninchen: katamnestische Betrachtung von 39 Patienten. Tierärztliche Praxis Kleintiere, 37(2), 107-113.

Schnabl, E., Böhmer, E., & Matis, U. (2009): Diagnostik und Therapie des Magenbezoars beim Kaninchen: katamnestische Betrachtung von 39 Patienten. Tierärtzliche Praxis, 37, 107-113.

Schnellbacher, R. W., Divers, S. J., Comolli, J. R., Beaufrère, H., Maglaras, C. H., Andrade, N., … & Quandt, J. E. (2017): Effects of intravenous administration of lidocaine and buprenorphine on gastrointestinal tract motility and signs of pain in New Zealand White rabbits after ovariohysterectomy. American journal of veterinary research, 78(12), 1359-1371.

Varga M. (2014): Textbook of Rabbit Medicine. 2nd ed. London: Butterworth-Heinemann Elsevier